(I’ve written a little about my childhood, about how our large family traveled extensively. That is why I was born in Spain, went to kindergarten in Nigeria, and spent months in Eastern Europe in 1975.

By high school I’d traveled a large part of the world with my parents, but I hadn’t been to China, understandable given the political circumstances, but my father had spent part of his childhood there, something I vaguely understood was due to his father, a military man with Jewish heritage, hoping to “wait out” the rise of Nazism.

During my two recent trips to China I became curious about those years, so I asked my brother Peter, the historian in the family, to explain. I thought it was interesting enough to include as a post, especially since I’ve been asked by various readers for more details.

This post is mostly written by my brother Peter, whose day job is in academia, despite my name being on the byline. Despite my extensive changes, he’s responsible for everything wrong in it, while I’m responsible for all the good parts.

PS: I leave Tuesday for Tashkent, Uzbekistan, then Xi’an, so the next few posts will be more conventional walking the world material. Until then, I hope you find this as interesting as I do.)

In the claptrap, cluttered, Victorian house in a permanent state of despair in which I and my six siblings grew up in rural Florida1, every room was stuffed with books, paper, pictures, and memorabilia from our global travels, giving the place the air of a disorganized small museum or, better, a thrift shop festooned with bric-a-brac items.

Amid the objects found everywhere—pottery shards from Mexico, religious art from Bolivia, West African sculpture, and endless collages of Polaroids from global travel—there was an even looser shamble of books, photos, and memorabilia that made my father’s home office a secret den, a collective pile of stuff from everywhere.

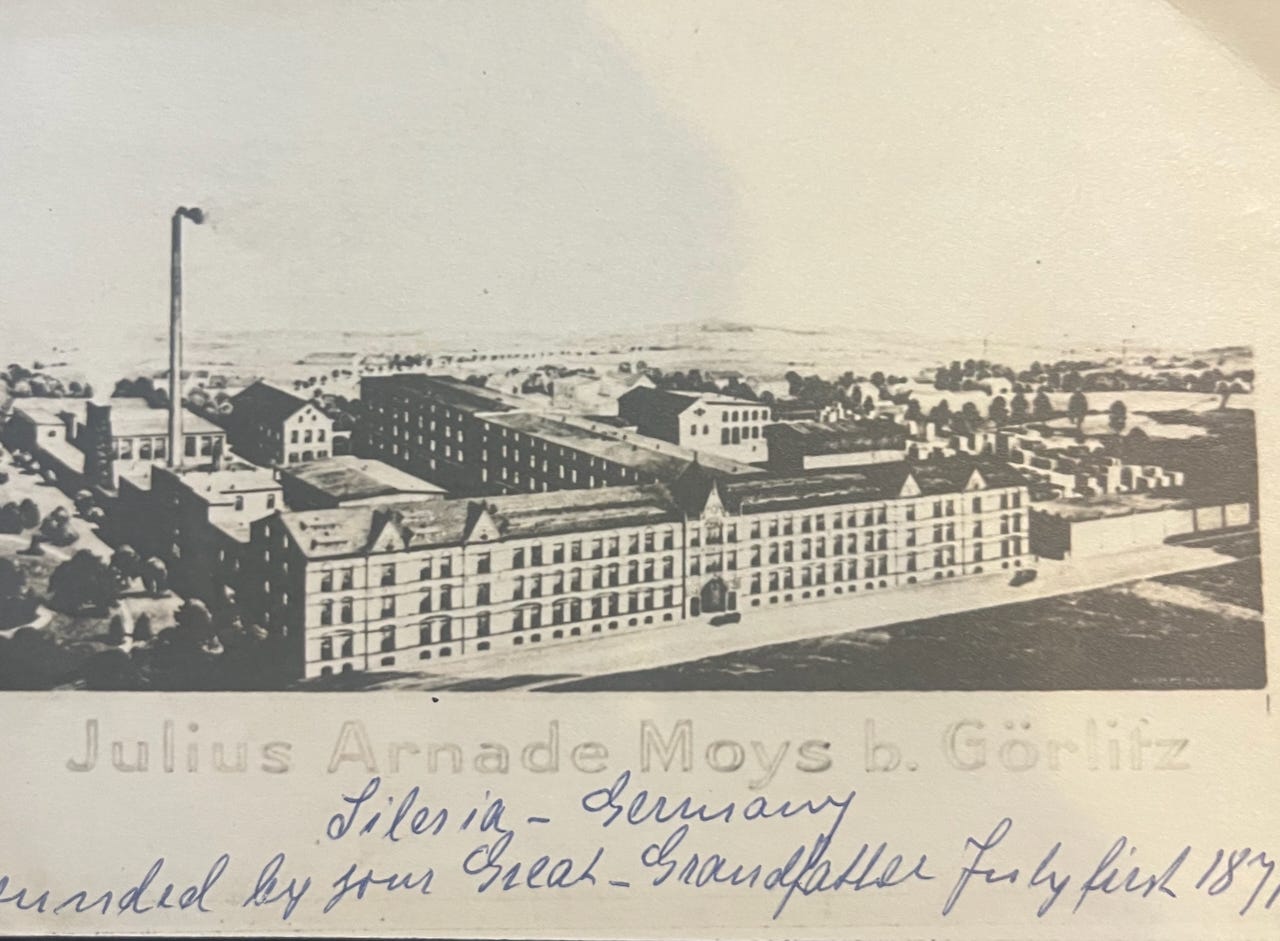

Featured prominently above his beloved shabby typewriter were two photos that stood out to me: one of an industrial factory with smokestacks and the other of a formidable German military officer, in full military getup, that to any young American kid looked straight out of a World War II film about the Nazis. This puzzled me, as these pictures were a jarring contrast to the “global south” parade of artifacts and books that defined our home life.

My father was a German immigrant, a gregarious, eccentric professor of international relations at the University of South Florida in Tampa, and a specialist in Latin America, an interest that fit him since he had spent his teenage years, during World War Two, in Bolivia. That much I knew, but little else.

We learned the first photo was of a suitcase factory his family had owned in the city of Görlitz, Germany’s easternmost city. The other was of his father, Kurt Konrad Arnade2, my Opa, who I only have a few memories of, since he passed when I was six.

Both pictures were snapshots of a very different past that my father, other than his thick accent, gave little hint of having. He dressed simply, almost slovenly, and while he had moments of personal regiment, he was also very loosy-goosy, to a fault. There was little in him that showed he had grown up very rich, very disciplined and structured, the son of a German military officer who was in line to inherit a luggage factory, and some ancillary mansions.

Both photos affected how I viewed my father, and they piqued my interest in our family history, and eventually that led me to medieval and early modern European history, which I’ve been focused on now for over four decades.

The study photo is probably from 1934, right before my grandfather went to China (more on that below). Prior to that he had left the military, following service as a captain in World War I, to help run the family business. He also spent a brief period in the notorious Freikorps, specifically the Reinhardt Brigade, where he fought against communist miners in the Ruhr Valley during the turbulent political clashes of the Weimar era. That is something, despite the current taint, he was never embarrassed by, since he was proudly on the Nationalistic Right, although also strongly anti-Nazi.

The fuller story I and my brother Chris only got in 1975, when our adventuresome parents, who had routinely flung all of nine of us around the world for long parts of our childhood—West Africa, South Asia, and elsewhere—chose for our next trip to spend a half-year in Eastern Europe behind the Iron Curtain3.

This was the peak Soviet era of the Eastern Bloc, and my memories as we traveled across Czechoslovakia, the former Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and East Germany, were those of a sepia-tinted experience of Soviet puppet regimes—faux Socialist authoritarian regimes of various levels of menace, with restless citizens furtively whispering to us about challenging living conditions.

The dourness of these regimes was made especially vivid by the disaffected older teenagers—I was thirteen myself and eager to be one of them—who smoked, drank heavily, and wore scruffy jeans jackets and boots, anticipating by years the UK’s punk movement and the US’s grunge-era rock.

It was April 1975—my brother Chris recalls hearing about the fall of Saigon on April 30 on shortwave radio there—when we arrived in Görlitz, my father’s hometown. He was forty eight at the time and had not seen it since his very brief return from China in 1938 at the age of twelve, before he was swept up in an eight-year refugee whirlwind, that sent him through Switzerland, Antwerp, Bolivia, and Mobile, Alabama, before finally depositing him in Astoria, Queens in 1946.

In Görlitz we spent most of our time with his mother’s family’s relatives, including an elderly uncle whom I only recently learned was gay and sent to a detention camp during the Second World War—and a cheerful high school teacher, Lotte, who was a proud local cadre leader of the Communist Party.

He, sombre and nostalgic, showed us photo albums of his relatives, including a young Nazi soldier who trained dogs, who disappeared forever near Stalingrad, and she plied us with cloyingly sweet teeth-breaking Eastern Bloc candy while running her fingers through my hair, sighing, tearing up, telling me that I resembled a family member who had perished in the Holocaust—a heavy burden for a kid from rural Florida more interested in life than past death.

Aunt Lotte’s revelation was news to me, not only of the details of the Shoah itself, but of having family who had died in it. While I sort of knew my father was in the US because he was a German with vaguely Jewish roots, he himself was hardly religious, and all of us children had been raised Catholic.

This soon changed, as we toured Auschwitz, with my father determined to find out what had happened to his relatives sent there (nine Arnades died in the camps, and a tenth in a Berlin hospital, after liberation, too weak to recover). He never did find out what had exactly happened to them, although I remember he kept muttering “I hope it was quick. I hope it was quick.”

The trip to Görlitz fundamentally reoriented my father. Upon his return, he shifted his academic interest to include conflicts across the world, not just Latin America. The joke in our family became, if you wanted to know where our next trip was, read the papers and see which place is currently the most F-ed up. He became especially interested in the peak of human awfulness, developing one of the country’s earliest classes on comparative genocides4.

But what about that Nazi-looking military officer whose picture intimidated me as a child? Kurt Arnade, my grandfather, Opa, was indeed a military man, a conservative, a far-right nationalist in his youth, and a proud admirer of Prussian values and of Bismarck himself, about whom he wrote a few admiring letters.

The Arnade family were wealthy Jews from Breslau and Loslau, now Wrocław and Wodzisław Śląski in Poland, but then in German Silesia. Sephardic Portuguese in origin, they refashioned themselves as longtime merchants and craftsmen settled in German territories of the north.

In 1900, the founder of the successful suitcase factory business, my great grandfather Julius Arnade5, left the Görlitz Synagogue and raised his children Protestant, even if the oldest two’s births are recorded in the local synagogue records. He became a very successful local businessman, a city council member, and proudly bore the title of “royal commercial counselor”—repeating that title regularly, as if it had proved the family had made it in the proper social circles.

My grandfather was the youngest of five brothers and the one designated for a military career—part of what I believe was Julius’s plan to elevate the Arnade name in traditional German fashion, proving they fit in, despite their soon to be hidden ethnicity. His vision saw his sons achieving prominence in business, law, politics, and the military.

The Jewish ties still lingered— the brother6 who principally ran the suitcase factory —was married into a prominent Jewish family who had a string of successful department stores. But it was more muted and receding, so much so that when Germany remilitarized in the early thirties, Kurt Arnade happily rejoined as an expert field engineer.

Yes, Hitler had come to power, but the Wehrmacht was still full of old Prussian loyalists and the senior officer corps, scions of conservative aristocrats from the older Reichswehr era, the kind of people Kurt Arnade admired and whose company he sought.

The Nazi enthusiasts were ruffians to them, lumpenproletariats, even if there were certain political convergences. An ugly lower-class sort of Nationalist that, while they might share some political goals, lacked the underlying moral codes of the past.

As the Nazis consolidated power across Germany's institutions and civil society, the Wehrmacht fell increasingly under their control. Kurt Arnade knew he was in danger, as it was an open secret that the Arnades were either converted Jews or still considered Jews. Kurt had, against his fathers consent, married a secretary from the factory. Her family was from the wrong side of the tracks, in almost every dimension he cared about. They were resolutely working class, socialist, and atheist7. But love is love, even for a military man determined to rise.

Oma, who I also only have a few early memories of, seemed to have more common sense than Kurt, urging him to leave Germany as the Nazis gained more and more power. Rumors increased that he was a Jew, including a scurrilous take down of him penned by a fellow military academy cadet, Hans Trost, who deemed him a lightweight dandy, wearing the fanciest military get-up his rich parents provided for him, and serial boaster, with a prominent “crooked nose.”

The dam finally broke in 1935 when an anonymous letter appeared in the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, accusing him of being a "full-blooded Jew" ("Vollblutjude") and claimed that the Görlitz Arnades were secret Jews who had infiltrated politics, business, and the military.

Now he knew he needed to flee Germany, but by 1936, most escape routes had been shut for Jews and those of Jewish descent. One fortunate opportunity remained—joining the German private military mission to China. Friends in his military circle, eager to protect a fellow conservative and veteran of World War I, strongly encouraged this move.

At the time, China was approaching the end of the Nanking decade of Kuomintang rule (1928-1938), which had begun with the 1927 purge of communists. Under Chiang Kai-shek, Germany became China’s top trading partner, and German influence ran deep, as Chinese officials admired the country’s 1871 unification, Prussian military strength, and Otto von Bismarck's statism.

Chiang, who had sent his own son to study in Germany, even appeared in a German military uniform during the occupation of the Sudetenland. His "New Life Movement" borrowed heavily from German nationalist and völkisch ideologies.

Between 1927 and 1938 over one-hundred German military officers assisted the Chinese Kuomintang under five different directors. The last of these, Alexander von Falkenhausen, had trained alongside Kurt as a cadet and became his supporter.

Their mission was to professionalize the Chinese military, establishing military schools modeled after the Kriegsakademie, and Kurt, an expert in military engineering and munitions, was assigned to Nanking after arriving in Shanghai with his family.

Kurt’s plan, if you can call it that, wasn’t unique. Some of the other officers sent to China were what the Germans classified as "Mischlinge"—individuals of mixed Jewish heritage—making the mission an escape route for Jewish military members fleeing an increasingly Nazified Germany.8

Von Falkenhausen was an old school, learned Prussian aristocrat, a man of letters and war, and an enthusiast for Japanese and Chinese history and culture. He did eventually join the Nazi party, but seemed in temperament out of alignment with it, though he clearly did not have the courage to dissent.

He is best known not as the last director of the German mission in China than as the head of the German occupation of Belgium in 1940, the same role held by his uncle twenty-three years earlier during the first world war. His record was deeply contradictory—he deported over 22,000 Jews, claiming he did so reluctantly and only under direct orders, yet he also took measures to protect some local Jews and resistance fighters. His actions eventually put him at odds with Berlin, leading him to support the failed officer coup against Hitler.9

Kurt spent two years in Nanking, which ended up being the most eventful and tragic in the mission's history. In December 1937 the infamous "Rape of Nanking" began following the city's capture by Japanese forces. The atrocities were staggering—tens of thousands were tortured, murdered, and brutalized, so much so that they outraged the German military mission, although that didn’t slow down the emerging alliance between Nazi German and Imperial Japan.

Kurt fought alongside Chinese troops north of the city, having already sent his wife, son (my father), and daughter to safety in Shanghai. Military records show that Japanese troops ransacked their home, though the damage was not severe.

In 1938, Hitler officially disbanded the mission and ordered all officers to return home. According to Kurt’s later reflections, he resisted leaving, but Berlin threatened to arrest and deport not only his two surviving brothers and their families but also his wife's family if he refused.

German military archives confirm this, though they add nuance. Some officers warned him against returning, deeming it too dangerous, while one supervisor even put in a good word for him with the Wehrmacht despite his "full non-Aryan" status. When Kurt finally decided to return, he requested passage via the United States, citing his wife's need for medical treatment, a clear ruse to attempt an escape.

That request was denied, and the family went back to Berlin grudgingly, mostly via a slow boat from China, along with other recalcitrant Germans, hoping by the end of the long trip the politics in Germany would have changed. My father, a young boy at this time, told a story about that boat trip, and how the anti-Nazi passengers named a pig on the ship Hermann, after Göring, which got them nasty side-eyes from the radio operator, who unlike almost everyone else on the boat, had fully drunk the Nazi Kool-Aid.

The politics in Germany did change during the boat trip, but for the worse, and after a chaotic few months in Berlin and Görlitz, Kurt and his family escaped to Switzerland with the help of the Quakers. After eight months there, they secured passage to Bolivia, where Kurt eventually found a job—much like in China—training military officers.

Bolivia started a new chapter for my father’s family in the mountain city of Cochabamba. That’s another story.

Later in life, after settling in New York City, and cobbling together a decidedly middle class, though intellectual, life (opening an Astoria candy store, working as a surgical nurse, and as part-time instructor in military history in Long Island), Kurt often reflected on his years in China. He continued to lecture, write essays, and submit letters to the New York Times on modern China and Latin America, all while longing for his homeland.

He visited Germany with a delegation of journalists in the late 1950s, but he never again set foot in Görlitz. His deep-rooted German nationalism never waned, yet he railed against the Nazi regime, which had destroyed his beloved Vaterland and murdered his brother Paul and other Arnade relatives solely for being of Jewish descent.

Despite all of that, despite the “fall” from being a German officer raised in a mansion to being a nurse living in a small suburban home in Middle Village Long Island, despite being steeped for decades in German Nationalism, he wasn’t bitter, and he loved America. It had provided him a refuge after twenty years of turbulence.

While my father taught courses on history for six decades, he only discussed his early childhood and this history in bits and pieces. But the pictures over his typewriter, his determination to visit his home town as he approached middle age, his academic and personal new directions afterwards, and his father’s papers, which I inherited after my parents’ deaths, on which he left some handwritten comments on the frayed, old papers is proof positive the past weighed heavily upon him.

From Chris

When I went to Shanghai, and Beijing, part of me naively hoped to find some lingering evidence of my grandfather’s time in China. I even thought about spending time in Nanking, but within a day, I knew that was a fantasy: I wouldn’t find any traces of his time there or even of the German presence.

The past doesn’t work that way. Aside from a few parts of Europe, most of the world eradicates the physical bulk of its history with surprising speed, holding onto only a few symbolic items that almost always become distorted, reshaped to serve the future by redefining the past.

History doesn’t survive that way, not in the built environment, not in ways that can easily be understood. Instead, it survives in the minds of individuals and in the stories they write down, share, or pass on to their relatives and friends. It is in the stories we tell about our own genealogy, our own family arc, where a history free from the spin of bureaucrats still lingers.

Nobody truly dies until people stop sharing stories about them. So while I didn’t, and never will, find any evidence of my dad’s or grandfather’s time in China, being there was enough for me. It brought back memories of my father’s study, made me search through my photos, and, ultimately, prompted me to ask my brother to write this.

Here is a paper written about my father, and other German Jews who eventually became historians!

San Antonio. For those interested. Home of the annual Rattlesnake roundup and gopher race. Yes, we raced turtles back in the 70s, when that wasn’t considered cruel. We even painted them and turned them into little floats, with various awards going to those who made the most impressive decoration out of a turtle.

This picture was likely taken in Ulm after he rejoined the military in 1934, during the height of Germany’s remilitarization

Only Chris and I, the two youngest, went on this trip, as all my other siblings had aged out into high school and college.

While he never did become religious, he did start speaking German more than his beloved Spanish and made a few trips to Israel, declaring it one of his favorite countries.

Born Julius Israel Arnade, if there is any doubt about his heritage.

Paul Arnade.

A family story my maternal grandmother told was that her leftist father would stand in front of a church or the synagogue in Gorlitz and proclaim that if God exist he should strike him down right there, and when nothing happened, he would loudly exclaim religion was a sham.

Chris here. I remember sometime in the early ‘90s, when I was working as a bond trader at Salomon Brothers, I was chatting to a salesperson across the aisle from me (as you do on a trading floor) who had stood up and asked if I was Jewish, since she heard me talking to someone on the phone about my father, and when I told her, it was complicated, but mostly, and then told her my father had been a German who “fled to China because his father was a German Jewish military man” she said, ‘Hey, that is the same story as my father!” As they say, small world it seems.

In 1944, he was dismissed for disloyalty and sent to a series of German detention camps, but then arrested and tried by the allies after the war, and imprisoned, even though some Jewish leaders including Leon Blum, the former prime minster of France, pleaded the case for leniency for him. His greatest champion was Qian Xuiling, a fascinating Chinese woman scientist living in Belgium with her Belgian husband, whose family he had known in China. She had originally appealed to him in 1940 to spare the life of a Belgian youth who had blow up a German transport train—successfully so as it turns out. She returned the favor pleading the case for clemency herself for him during his trial after the war, unsuccessfully. Her story was compelling enough to inspire a 16 episode television series about her life in China.

A tremendous story and well told. It answers a question or two that occurred to me reading Chris’s reports over the years in which he made references to calling the Jews “his people,” and then in another story talking about his Catholic child hood. I thought, “Which is it Mister?!” Well, both, as it turns out.

Fascinating story, Chris. Easily the makings of a novel.

My grandpa was a Greek Jew from Thessaloniki (Salonica) who survived the purges there, joined up with an American army attachment during WW2 as a translator/spy (he was gifted with languages) and eventually went to Chongqing to help the US and Chinese Nationalist forces at the tail end of the war because he somehow taught himself Mandarin in a year. He left when Mao took over.

He ended up running the American Bar Association back in the US after a long career in law in NYC.

They don't make old people like they used to!

Also, this was an enjoyable, fast-paced novel about Jews fleeing to Shanghai during WW2. Came out last year:

https://www.amazon.com/Shanghai-Joseph-Kanon/dp/1398519774