(My two prior walking Germany posts: Walking Ruhr Valley, Walking Rhine Valley)

The last time I was in Görlitz I remember listening to the fall of Saigon1 on the radio, told in glorious terms by an East German broadcaster that even at ten I knew was the language of propaganda. Western imperialism chased out like a mangy dog by the peace-loving proletarian masses.

I don’t remember much else from those four months visiting my father’s relatives behind the Iron Curtain, beyond a few such images, and my mood, which was despondent. A sense of being in the middle of something sinister, where all the colors were dull and gray, and the people furtive and conspiratorial. The only moments of joy coming from things every ten-year-old finds pleasure in, a visit to a zoo, the rare ice cream at night, or taking solace from candy given to me by relatives who smelled of dirt and moth balls, patted me on the head like a farm animal, and admonished me in German.

I’m told when we finally arrived in Vienna, after a night detained in a cell at the Austrian border2, that I literally kissed the ground, telling my parents it was like God finally had his full range of colored crayons back.

Exactly forty-eight years later I’d come back to Görlitz, pulled partly by nostalgia, partly by family history, but mostly by boredom. I’d finished my walk from Dortmund to Cologne faster than I’d thought, and I wanted to see something different. Not another continental city jammed with binging Brits.

Görlitz is not that, rather it’s jammed with middle-class Germans binging on history. Well, the history prior to WW2.

Görlitz has changed a lot. Communism is gone, Germany unified, and the world is different. What hasn’t changed is its look. Görlitz, due to the quirks of history, was never physically touched by the war; it wasn’t bombed or shelled. Then communism’s incompetence froze it in amber for forty-five years, leaving it, post-unification, a tourism gold mine. The rare small German town that could draw a barely interrupted line back to the medieval. A quaint storybook place of cobblestone streets, fountained plazas, and cathedrals that hum Bach.

A Germany before the awfulness.

Once a town of merchants and border trade, it’s now a town of leisure. A place where upper-income Germans buy second homes, and where buses of retirees spend the day snapping hundreds of pictures of things that everyone else has snapped a picture of, presumably because that’s what you’re supposed to do.

That’s made it a very transient town, with little sense of place, beyond the sense it is the kind of place that must have an important sense of place. Making it more of a museum than a town.

That transience and coldness hit me especially hard, because after I’d spontaneously booked my trip, I built up a silly little fantasy that maybe I would be recognized in Görlitz, maybe even welcomed, because of my name. Which was a refreshing idea after eight days of walking through towns as a complete outsider.

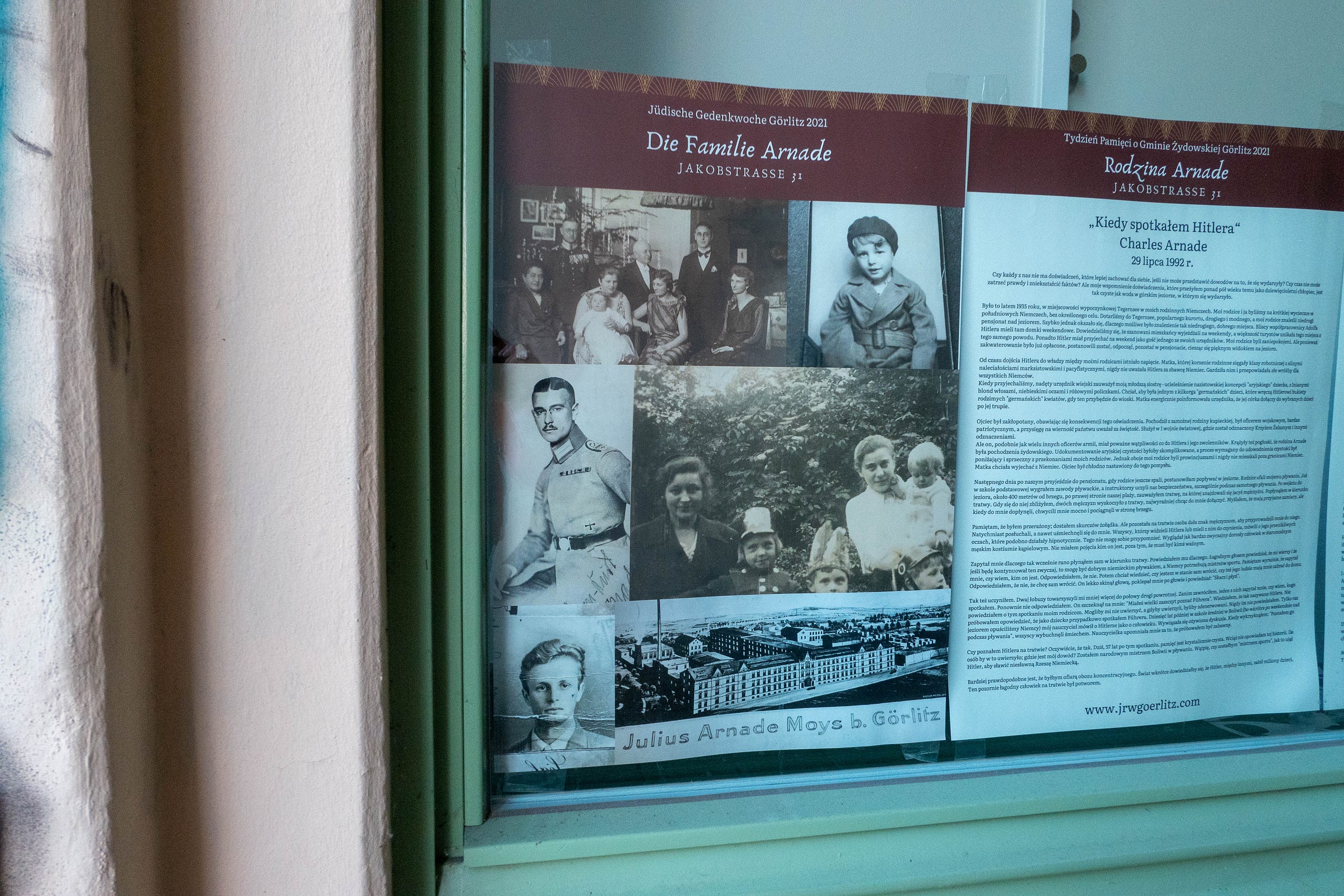

My great grandfather had been something of a bigwig in Görlitz, a poor kid from Poland who had made good. He’d come across the border and built the biggest steamer trunk factory in Germany, integrating himself into the local elites by joining civic associations, building a church for his workers (despite being Jewish), and buying himself and his kids mansions on the correct streets.

It was an attempt by a poor Jewish kid from Poland to be accepted in German high society, and it worked, until it famously and horrifically didn’t.

As my brother, the historian in the family writes,

In many ways, the Arnade story in Gorlitz is a story of German Jews of that era. Highly ambitious, successful and assimilated, they cast their lot with the nationalists, conservatives, etc. They did everything to assimilate, including placing the youngest son, our grandfather, into the military. But it came back to bite them, for what was worse in the 1930s than a Jew, were secret Jews passing as something else. They got slaughtered. Three months ago I found in the Nazi notorious newspaper of the era a denunciation of the entire family as fake Germans—clever Jews passing themselves off as something else. The family was doomed—well off, etc, they got hit hard.

My grandfather hadn’t ever liked the Nazis, and while he was largely conservative, it was in the direction of the Monarchist and nationalist, rather than the fascist, and so when the winds changed in the early 30s, he quit the military, and took his family to China, where he served as military advisor to Chiang Kai-shek’s army3, before eventually making his way to Bolivia, then the US.

His two brothers4 stayed in Görlitz, where one of them somehow survived5, while the other was killed in a camp along with his wife.

Post unification there was something of a reckoning with the past in East Germany, which had brought my dad to Görlitz for ceremonies and to file paperwork, or decline filing paperwork, to recover lost assets.

I thought all of that would give me a place in a city that now has little of that. But within a few hours that idea was exposed for the silly fantasy it was.

Görlitz is small, so it took me only hours to visit what is left of my family there. To see the Stolperstein for my father’s uncle Paul and aunt Margaret. To read the small sign of Arnade history next to it. To walk in the park across from where they had lived. To visit the two old Arnade mansions (one fixed up and lived in by strangers, another owned in name only by a distant cousin of mine), and then to cross what is now the border to Poland, and visit the factory (now used for making bedding) and the accompanying church my great grandfather had built.

I was the only person during that whole weekend stuffed with tourists who ever looked at the Stolpersteins. It was all so cold and distant. Small touches to the awful past, nicely done, but without any connection to the community. At least that I could find, or feel.

After I’d done that, there wasn’t much left to do. It was May Day weekend, and the only things open were for tourists. Shops selling postcards, cafes, bars, and restaurants, none of who cared about that past beyond a thing to make money from.

So for three days I did the same circuit of family history, getting more and more glum each time, my mood not being helped by reading the family histories behind the Stolpersteins I stumbled across. Like that for Paul and Margaret,

Paul Arnade and his wife Margarete Arnade owned and operated a suitcase and leather goods factory in Görlitz, which Paul’s father Julius Arnade founded in 1872. His business profited from a prosperous economy and increase in tourism. Julius Arnade died in 1915 and his tombstone can be found in the Jewish Cemetery in Görlitz. Paul became chairman of the tourism association in Görlitz, but was pressured to resign in 1933 because he was Jewish. In 1936 the family was forced to sell the factory for a paltry sum. In 1941 both Paul and Margarete were sent to the ghetto in Tormersdorf. Paul and Margarete were both deported to Theresienstadt in 1942 where he died at the age of about 68. Margarete was killed in Auschwitz in 1944 at the age of about 58

Or for the Oppenheimer’s down the block,

Erich Oppenheimer and his wife Charlotte Oppenheimer lived with their son Werner Oppenheimer at Jakobstraße 3 in Görlitz. Erich was a doctor born in Berlin and his wife was born in Görlitz Moys. All three were sent to the ghetto in Tormersdorf in 1942. Erich and Charlotte committed suicide by drowning themselves in the Neisse River to avoid being deported at the ages of about 48 and 46. Their son, about 21 years of age, was sent to the ghetto in Lublin in 1942. His fate is unknown.

To add a touch of absurdity to the gloomy weekend, my sandal broke. The strap on the right shoe gave way, and for two days I had to stagger slowly, past closed shoe stores, past closed hardware stores, past anyone or anything that could fix it. Like an addict past drugs he couldn’t snatch.

It turned into a cartoonish inner dialogue, me shuffling around a small town on a three day weekend, when everything is shuttered, trying to get my fix. Trying to figure out how to rectify my situation. I eyed garbage cans for discarded foot-ware. I sussed out the local drunks to see if their feet were about my size. Maybe they’d swap shoes for $50? I maliciously surveilled the street shoes of the athletes lined up along the side of the soccer pitch.

In the end, I found a shopping bag in a junk pile, pulled out the string handle, and fashioned a makeshift strap, which wore away thread by thread, mile by mile, till only a thin fray was holding it tight.

It became a quest that occupied my mind, enough to replace the depressing thoughts of the past. The story after story of horrific deaths, now turned into places for tourists to ignore, or snap pictures of and then forget.

Focus on the shoe, not the deaths, not the realization that nobody really cares about the bad part of the past. That the Nazi’s had won. That they’d sent a country into a killing frenzy, destroying my fathers’ family, and so so many others, and eighty years later the only signs of their sins is small brass memorials and a cold soulless town that periodically cosplays that past for the movie cameras.

Film is the other thing, besides second homes and tourism, Görlitz now makes money from. As a place to shoot movies, especially ones about the Nazis6.

That is unfair of me though. Görlitz is a beautiful city, and I’m not sure how they or we should, or could, reckon with the past. You can’t hold grudges or guilt forever. History doesn’t work that way, and neither do people.

You move on, because as it was said in a ponderous voiceover I’ll never forget, from an awful 80’s Sci Fi movie, “Time passed, as time often does.”

Nobody in Vietnam held me accountable, or even cared, for what we did to their country. Nobody went out of their way to notice I was from the US, other than to celebrate it out of genuine warmth and curiosity.

Nobody in Görlitz went out of their way for me at all, beyond being another tourist snapping pictures of the magnificent buildings. Which makes perfect sense, because for all practical purposes that is what I was.

I’m not sure what I was expecting to find in Görlitz. Closure is a dumb concept, that assumes the world, and humans, are far more mechanical than we are.

I’m not sure why I was so down the whole time. I knew, logically, all of that, yet I was still miserable.

Maybe it was the beauty of Görlitz that was my problem. In my old co-op in Brooklyn there was an elderly couple, Ruth and Arnošt Reiser, who had both been in Auschwitz.

I used to try and visit them once a month, to have tea. We rarely talked about the past, except when they brought it up, which wasn’t often. One visit however, some special anniversary for the liberation of Auschwitz was in the news, and they mentioned they were invited as special guests, etc, but couldn’t travel because of their age. Then Ruth said, something like (I’m paraphrasing), ‘Well, we have no interest in ever going again. We went to one of these invitations once, and it was too clean. Too sterile. Auschwitz was never ever clean. It was mud and blood. Not a museum.”

Maybe, in some small way, that was what I was expecting to find. Filth not beauty. Or at least not pre-packaged sterility.

Again, that is completely unfair of me. Görlitz, only to me and a handful of people, is a place of bad things. It’s no different than any other German town. Or Polish town, or almost anyplace in Europe or so much of the world. History is littered with bad things, and it’s wrong to completely expect them to stop, frozen in pain, for you. Or for anyone else.

Because, once again, “Time passed, as time often does.”

April 30th, 1975

My parents, me, and my brother, were pulled off the train at the Czechoslovakian/Austrian border, and put in a jail cell, while four bored looking crossing guards went through all our luggage. They took away my little plastic army men, and my mom’s collection of New Yorkers she would bring on our trips. They threw the army men in the trash, and read all the New Yorkers.

After 10 hours or so, me and my brother were brought to a candy store, given treats, and then all of us were allowed to get on the next train to Vienna. There was never a reason given for our detention, beyond something about “papers.”

My father spent much of his childhood in Nanking, before the family was called back to Germany by the Nazis under threat of death. They fled to Switzerland, then eventually Bolivia, then post-war, New York City. Astoria, Queens to be exact.

Two other brothers died young, of natural causes.

That line of family moved out of Görlitz before Communism came.

Inglorious Bastards, among other period films, was partly filmed in Görlitz

A scene from "Judgment at Nuremburg" comes to mind. The American prosecutor, played by Richard Widmark, implores the husband of a witness he wants to testify at the trial, angrily telling him "They must not be allowed to get away with what they did!". To which the husband sadly says "And in the end, do you really think they won't get away with it?". Such it is with history.

It's interesting that none of these Stolpersteins have yet been placed in the Channel Islands, the only part of the UK to have been occupied by the Nazis.

Since the end of the War, the British government has systematically repressed information about what happened there -- on the not entirely unsensible grounds that public knowledge about who collaborated and who did not would lead to a culture of reprisals amongst the tight-knit families living there.

This policy (possibly not coincidentally?) appears to have given at least one very prominent political figure in the Islands a free pass.

This odd silence encapsulates entirely the tension between Forgetting and Remembering. The wartime generation were in some ways very big on forgetting and moving on. When they remembered, they mostly celebrated -- the courage, the sacrifice, the sense of a shared struggle. It was an attitude perpetuated by the deeply selfish Boomers.

It falls to our X generation and later to remember in a more complicated way. And a kind of 'reverse flip' (European history = all bad) isn't good enough. I guess the struggle to find an adjustment that both honours the past and is something that allows us to live in sanity, on good terms with ourselves, will continue to generate some excellent writing though.