America, the beautiful

We are still a great nation, despite what I usually write

Looking back at my posts for the year, the three best performing were all negative essays on the US, topped by my dystopian take on Phoenix. The second most popular was arguing Europe is healthier than the US and the third about the death of the American Dream. I did write two more positive pieces, one arguing the world doesn’t hate America, and another explicitly stating the US is better than Europe, but neither resonated like the pessimistic pieces.

I stand by all those pieces, yet sometimes you can miss the forest for the trees, or the beauty for the addicts clustered on the street corner. The US is still a great nation, and it’s where I choose to live, not out of necessity or inertia, but because I want to be here. I want to be here for its wealth, its vastness, its independence, its openness, its convenience, its safety, and most of all for its optimism, which while hard to see at times, is there, simmering beneath the surface drawing the hopeful of the world, like moths to a flame, to line up at our embassies hoping to get a green card and a chance at a better life.

That optimism is present even in some of the most dystopian scenes, and even in my most negative pieces, like Caroline in Bristol, who while living in a shelter hiding from an abusive ex, had gotten up early on a Sunday morning to apply for a job at the McDonald’s.

Me: So the question I ask everyone is, what’s the American Dream?

Caroline: Kinda just be happy, be free, and be able to live without worry honestly.

Me: Do you think it’s still available?

Caroline: Yeah, you just got to work for it.

Me: You’ve been through a lot for you to believe in the American Dream. That’s pretty impressive.

Caroline: (laughing) I’m trying to. What else can you do?

Me: Some people don’t, and turn to drugs, which you haven’t. How?

Caroline: Been learning and seeing my whole life what drugs can do to you and cost you, and no.

Phoenix is no different, and while the optimism is hard to spot in the worst corners I highlighted, it thrives only blocks away, in the two square-miles of twisting single-lane roads lined with simple ranch homes of lower middle class residents working on their version of the American Dream.

The opening photo is an example of that: A simple home, that while rough looking, has enough small details of care — the flag, the small statuary — to show that whoever is living in it is probably doing their best to improve their life, and probably generally content because they have a home, a yard, a few cars, and with enough hard work their kids will have it better than they do.

The US, compared to the rest of the world, is optimistic because it is still the land of possibilities. You can remake yourself here, because we are generally forgiving, and provide everyone many chances to reclaim who they are. We don’t only give second chances, we give third, fourth and fifth ones.

Some of that is because of our size — there are many different Americas in the same nation, and if you fail in one, you pick yourself off the mat, move to another America, and try again. Some of that is from the Judaeo-Christian notion, baked into our nations culture from birth, that while humans are fundamentally flawed they are also gifted with free will and capable of transformation. Nobody is perfect, and while perfection can never be achieved, not at least here in the city of man, you can, and should, work towards it. The US, with its wealth of possibilities, provides many different routes you can take.

That pervasive sense of what is possible is missing from a lot of the world, where the focus is more on what can’t be done, or what shouldn’t be done, which is why our current biggest political issue is debating what to do with all the people who want to move here. We have an embarrassment of possibilities and riches, and despite all of our problems, that shouldn’t be forgotten.

We are an ideal for a large portion of the world, and while that ideal isn’t always a reality that we live up to, very few people come here, then turn around and go back, because with enough dedication, you can create your own form of fulfillment here. The US is a vast federation of micro communities and micro cultures, all bound together by the belief, however tentative and nebulous, in the American Dream.

The idea that anybody, with enough hard work, can be successful, without having to break the rules. That someone can come to the US from literally anywhere, with nothing, and build a life for their kids that’s better than their own.

In contrast to Japan, cultural change rather than preservation is our national model, and entrepreneurial-ism is our national identity. So much so that we have made it a transcendent and spiritual ethos, even though it’s grounded in the material. A nationalism built around a kind of prosperity theology — which is inclusive of different peoples and cultures, as long as they buy into the concept of aspirational wealth.

“What a nation is” sounds like a silly question, but when you think about it further, there is no widely agreed answer, not in the modern era where borders hold many different cultural and religious groups.

I’ve been reading Benedict Anderson's "Imagined Communities", whose thesis is that nations are "imagined political communities" because members will never know most other citizens, but in the name of them, they will do selfless things, like pay taxes, and violent things like go to war and kill for them.

He suggests that to pull off this “trick” there has to be,

A standardized national language

Mass literacy and print media

Territorial sovereignty

so that a national consciousness, spread through higher institutions and media, can be forged.

I don’t like this book, at all, not because I believe his thesis is incorrect, but because he sees this as not only foolish, but incomprehensible. He doesn’t understand why anyone would love, and die for something he views as effectively a big lie, which he sees as another version of Plato’s noble lie, a myth maintained by the elite to maintain social harmony. An opium of the masses thing.

National consciousness exists, and it does provide people with deep meaning. People need meaning that is connected to society, and nationalism is one of the last forms that we have in this increasingly secular, uniform, disconnected, and transactional world.

It’s a fundamental misunderstanding of the human condition to suggest that people can’t, and shouldn’t, believe in anything beyond themselves — that people don’t need a higher purpose that they will give their lives for, which extends not only to others they have never met, but survives after their own death.

That adulation of the self is at the root of many of the problems I document in the US. It results in an existential loneliness and emptiness that is the hallmark of a nihilistic despair.

While America does have too much of that currently, and I would argue we as a nation need to re-adjust our priorities, it still largely works because it historically has found the right balance of providing a shared meaning, while also allowing for a degree of flexibility, freedom, and uniqueness that’s lacking in other nations.

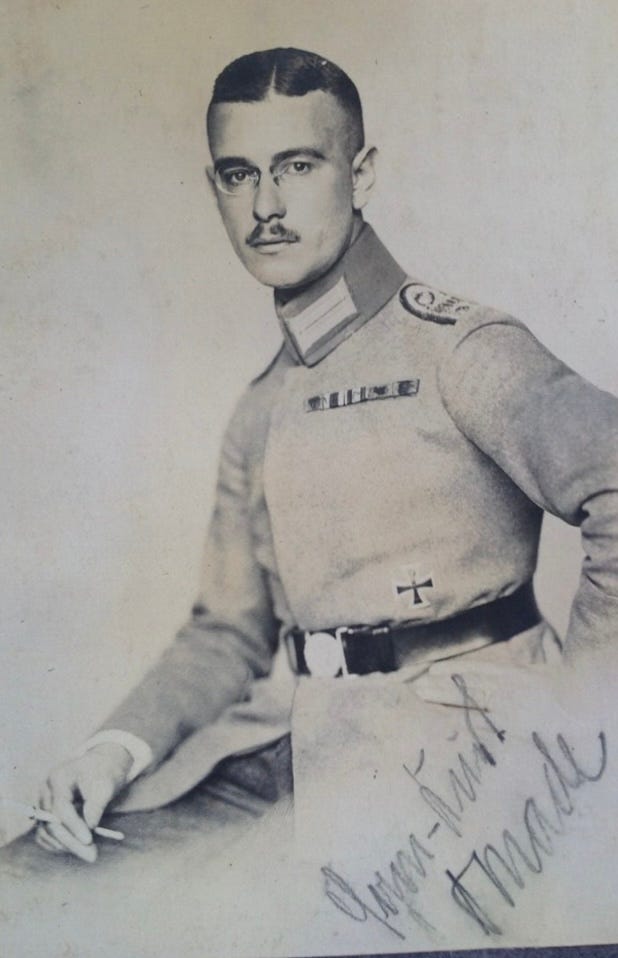

My being an American citizen is an illustration, and result, of the allure, strength, and flexibility of the imagined community that is the US. My grandfather, on my fathers side, was a high ranking member of the German military, from a very wealthy family of industrialists. He lost all he had, including all his wealth and many close relatives, in the second world war, and had to flee to Bolivia in 1939, where he worked with the US military who, as a reward, gave him US citizenship.

He eventually made it to Astoria, Queens, where, with little money and a family to support, he ran a candy store and worked as a night nurse, before eventually saving enough to buy a small ranch-style home in the middle of Long Island and retire to write pro-America op-eds in the local German newspaper.

I never met my grandfather, who died just before my birth, but I did visit his Long Island home with my parents, and when I saw how small, bland, and banal it was, I asked them if he ever was bitter about all he had lost. My mother laughed and said, no it was the opposite, he absolutely loved his house, and was so proud to be in America that he made it a great source of pride to always, and properly, fly a flag outside his home, no matter the conditions. America not only had literally saved his life, it had given him a chance to remake himself, and safely raise a family, which he never forgot.

I think of that house, and his story, when I see the cover photo, or any small home in the US, especially one flying the flag, no matter how rough the conditions are around it.

There is still a transcendent nationalism in the US, even if we have deep problems and ugly flaws, because the people have faith in both themselves and something larger than themselves, and America, at least for the time being, understands that.

That isn’t to deny, ignore, or paper-over the many social and political ills we have, which I’ve written about extensively, but as a reminder that every country has issues that need to be addressed, and I, like most citizens, am grudingly optimistic that we can, and will, do better.

I’m sorry this piece took a little longer to write, and is a bit different, but I’m planning on being home for all of January, since I’ve been traveling non-stop for close to three years now and I want a break so that traveling doesn’t feel like an obligation.

I’m leaving at the end of the month for a round-the-world trip to Dubai, Oman, Dhaka, Kunming (China), Beijing, Seoul, ending in Washington DC on February 27 to give a talk in a McDonalds!

As always, if you are in any of those cities, please reach out to me, and we can either have a coffee, or go for a walk. Have a great 2025!

Having just finished a two-week visit to the U.S., I agree with much of what you say. But for me, this visit highlighted how badly the social fabric of America seems to be fraying. We saw grocery stores, both large and small, being treated like fortresses because shoplifting is so bad. We saw empty storefronts in the heart of major U.S. cities like Seattle and San Francisco. And most worrying of all we saw how driverless cars, mobile phone orders, DoorDash and UberEats, and especially our ubiquitous phones are increasingly isolating and insulating Americans from even the most basic contact with their fellow human beings.

Beautiful tribute to a beautiful country. Your writing on McDonalds in TFP was incredible too. Look forward to vicariously living through another year of your travels.