Walking Phoenix

A quick retreat from an expansive hell on earth

The contrarian in me wanted to like Phoenix, and for the first twenty minutes I did like Phoenix: The airplane view of a Dr. Seuss-ian landscape of jagged red rock mountains plopped randomly amongst an endless street grid, the clean spacious airport with the cheery cashier who swapped a twenty for singles to use on public transit, the free Sky Train that glided me to the light rail station, the cool afternoon air on the platform wrung empty of any oppressive east coast humidity.

Before I could figure out how to pay, my train arrived so I hopped on it. I wasn’t worried though, I’d already downloaded the Valley Metro app, bought a day pass, and should that not work, I had crisp dollar bills in my shirt pocket ready to whip out. Anyway, nobody else seemed to be paying, so I sat down content and excited, happy to be back on the road for a month, and ready to undermine Phoenix’s stereotype as America’s least walkable city.

That was the high point, and within a minute it all started going south, kept going south, until I was so broken, despondent, depressed, and ill, I turned tail and went back home, barely batting an eye at burning a round trip ticket to the Philippines.

A wrote a minute, but it probably was only twenty seconds before the guy sprawled over three seats directly across from me, who smelled of shit, piss, sweat, and alcohol, started yelling at me. Telling me to stop looking at him, to get out of his face, and asking me why the fuck I was near him. He was a black guy, which I only mention because he mentioned it many times while also pointing out I was white.

I did my best to ignore him, but he refused to be ignored, so I told him something like, ‘It’s all good. I got no issue with you, we all cool,’ to which he said something like, ‘Well I got a fucking issue with you’ and leaned in closer, and ranted some more.

I causally looked around, hoping to find someone to share a look of ‘Geez, what’s up with this guy,’ but everyone was smartly ignoring it all, refusing to look at me, him, their eyes focused on being empty and removed. So a few stops later, when I realized he wasn’t going to drop it, whatever it was, I moved a few cars away, but he kept looming, and whenever I glanced up, he was locked on me.

Half an hour later I was at a bus stop, waiting with a mob for the 41 that was twenty minutes late, wishing I’d peed in the airport because this whole airport to motel adventure was taking longer than my bladder had expected. Given the surrounding smell I was sure my predicament wasn’t a novelty.

I was still optimistic and content. Phoenix has a muscular low-slung minimalist beauty, especially towards sunset, when the dust that coats everything gives back a little, turning the sky a soft red. The crepuscular lights hide a lot, and like a bottom rung strip-club, Phoenix especially benefits from that.

When my bus eventually came, it was so late, so crowded, the line to get on so long, the driver waived us through, so I didn’t get to use the bus app or the dollars in my pocket, didn’t get to bask in being the good student who’d done his homework.

Ten minutes later, about a mile from my motel, I was off the bus, feeling queasy from the odor of weed mixed with an undetermined burning plastic smell that seemed everywhere. Anyways, I was happy to walk the last few blocks and maybe find a place to eat that had a bathroom.

But there were few appealing places to sit down and eat, and no place with a bathroom that I could slip into to pee quickly — all were locked tightly. I quickly understood why. I was in an open-air drug market that extended the six-miles length of my bus ride, with dealers and users lining the road, their stalls being shopping carts piled high with boxes, bags, electronics, jugs, stuffed animals, mops, shovels, tents, and dirty clothes. The ground around them was littered with two-inch squares of burned tin foil, empty liquor bottles, old panhandling signs, and piles of shit and puddles of piss.

After crossing an overpass, its narrow passage a dystopian scene of bodies twisted into collapsed shapes from drugs, I was at my hotel, behind a guarded gate. In front of it was the restaurant I’d picked out as a fallback should I run out of time, which I was, and while it looked promising, it also had a large cardboard sign on the door “Bathroom Out Of Order” which while disappointing my bloated bladder, my brain knew was a ruse to drive away the overpass dwellers.

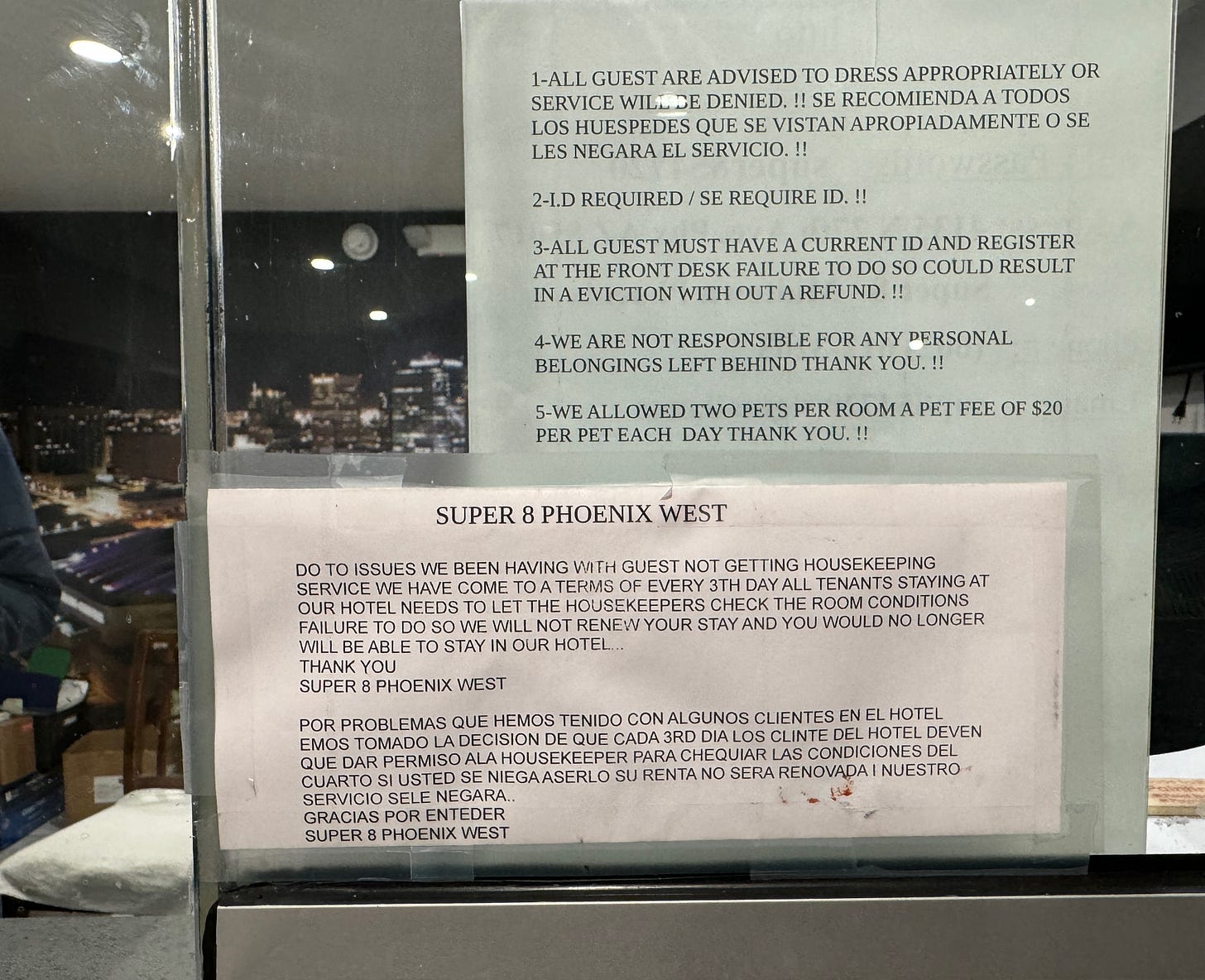

After a nice meal of pozole, I checked into my motel, and while I’m used to the chaos of cheap motels, which are often long-term residencies for people with state vouchers, this one tested even me.

The rooms had a strong prison cell aesthetic, stripped of anything valuable, that might cause harm, be broken, or carted away. A cement rectangle holding two hard beds with a single see-through thin sheet, a perfunctory cover that somehow was both scratchy yet provided no warmth, pillows so thin a stack of four barely registered as an adult pillow, and a decade-old TV bolted into place, and that was it. No lamps, no working outlets beyond one for the TV and fridge, which I unplugged so I could charge my phone and computer.

Then there was the smell of weed and that burning plastic, so I kept the door open, to be serenaded into sleep by the whoooshing sound of the Quick Quack Car Wash fifty yards away. I eventually closed it when the ambulance sirens got to be too much, and for safety, although its half-broken lock seemed entirely symbolic.

The next morning (5 a.m.) I started what I hoped would be the beginning of a daily routine, walking a mile to the McDonald’s to have my coffee and chill. But that walk, like the walk to my motel, was a maze of broken people. Now mostly sleeping, but many still up and hustling. It became like one of those old Disney rides, where an animatronic character would pop out from behind a building or bush, holding a bottle of vodka, or an old vacuum cleaner (why), or pushing a train of carts, and mumble something at me, or towards me, or just into the void.

The McDonald’s wasn’t much better. A haven for the broken. There was the woman who was engaged in a loud conversation with a Susan, who wasn’t there. She had no phone, but pretended she did. She walked around the dining room, never straying too far from her nest, a pile of bags and clothes near the kids’ playhouse.

“You’re the illegal, you’re the stranger in our land, Susan. Is you’re grotesque friend also an illegal Susan!”

(long pause)

“With your husband behind bars you don’t have citizenship, Susan. You’re trying to get me really hurt, Susan. Should I go to Uncle Mike’s apartment right now and knock his door? (pause) Why is your father allowing you to treat everyone in the family like such pieces of crap? (pause) Huh, Susan? Huh? Why aren’t you answering me. (pause) I don’t see any reason they should be lenient with you, Susan.”

When she started mixing in Friends references, “Well Susan, I’ll tell you this, I’m the Rachel character and you’re the smelly cat downstairs character.” I did my best not to laugh.

After my coffee, I began my planned walk, a thirteen mile loop that would take me through most of Northwest Phoenix, where I’d hoped to find something different, but I didn’t.

Six miles later, my ability to find humor in the disarray was gone, when desperate to pee, I went to an empty strip mall to add to the urine smell.

That’s where I found John, wrapped in a singed blanket, his body covered in scars and recent burns. He was alternating between picking at scabs and pulling smoke from a sizzling blue paste spread over a thin tin-foil bespoke stove.

He was smoking a “perc 30,” a cheap knock-off opioid pill. The legal term is non-pharmaceutical fentanyl, or NPF, and they’re all over Phoenix. They’re why the buses, and my motel room, smelled like burned plastic, since users pull the smoke up through restaurant straws. It’s also why my iced coffee at McDonald’s didn’t come with a straw.

John had (accidentally) set himself on fire a few days earlier, but didn’t go to the hospital, and refused my offers to bring him to one. He didn’t want to lose his prime spot, or risk having his drugs taken away, or being shuttled into another rehab where he would have to play by someone else’s rules.

I brought him a McDonald’s breakfast, although he didn’t eat it. He wanted to tell me his life story, of his “trauma,” which in his mind included having been a marine, a POW, and a sex-slave, all of which he escaped by swimming across the ocean1.

The more believable parts of his bio was he’d been born in California to a mother who cared more for her drugs than her children, followed by a decade in the foster care system.

John, like a lot of users I talked to in Phoenix, was slow. Very slow. Probably mentally disabled. In any functional humane society he wouldn’t be on the streets, smoking fake fentanyl laced pills and setting himself on fire. He wouldn’t be telling stories of trauma, real and made up.

But that’s not us. We, for whatever reason, let this crap happen. Churn out millions of Johns, untethered, with no community to embrace them other than the community of drugs and homelessness. We let whole parts of our cities become public shooting galleries, drug traps, and camp grounds.

The rest of the walk didn’t get any better, and my mood kept getting worse. The sun rose, my skin baked, and while I should have drunk lots of water, I didn’t, because there weren’t any bathrooms around. That shouldn’t have stopped me, because everyone else pee-ed and shit outside, turning Phoenix into the world’s largest litter box.

That first day’s walk wasn’t uniformly bad though because Phoenix does have nice parts.

Phoenix is a large grid, of mile-long four-lane sides, with shopping plazas at the corners, and an inside of twisting single-lane roads and simple ranch homes on half-acre plots. Those residential insides are the nice parts, and showing that they’re nice is partly why I’d come to Phoenix: to highlight a version of the American Dream, which, while I might not love and isn’t necessarily “walkable,” is still very appealing to lots of people. It’s what I wrote about last week, when I cautioned that walkability doesn’t necessarily translate into livibility.

Yet, it gets harder and harder to focus on those nice middle parts, when the disorder on the edges and the nodes was so overwhelmingly intense.

By the end of the day, I was a little beaten down, tired, sunburned, and dehydrated, but still ok. So I went to a local bar, had a few beers, got some tent tacos, went to sleep, and got up to do it all over again, this time with the plan of walking towards the presumably nicer downtown.

The second morning began at the same McDonald’s, with the now familiar woman yelling at Susan — my own little Groundhog Day-like riff (“Okay, campers, rise and shine, and don't forget your booties”) which I chuckled at.

By noon I wasn’t chuckling anymore. The walk, although in a different direction, was just as depressing. Long empty stretches on mile-long blocks, with just me and the distraught. It became another day-long lesson in the zoology of American dysfunction — the homeless addict, the mentally-ill homeless addict, the bored and aimless teens, the elderly with no family, the physically handicapped, the obese, the obese physically handicapped, the perc 30 addict, the angry mentally ill, and so on and so on.

After a lunch my body had no interest in, I realized I was in over my head, and needed to get out of the sun, needed water, so I called it quits, and found a bus route to get the six miles back to my motel. The first bus was running forty-five minutes late, and the stop had no shade, so instead of waiting, I walked to the second, which was an hour and fifteen late. I also walked that last bit.

When I finally got to my room, I realized I’d made a massive mistake2. I had zero appetite, despite having eaten little all day, and I badly needed hydration, so I went to the corner 24 7 Convenience Store to stock up on Gatorade, where all my cards were declined, then locked. I’ve used these cards in Senegal, Mongolia, and Ecuador without triggering so much as a security text, but the corner of 27th and Indian School Rd was too much for the algorithm. Given who was around me and the amount of plexiglass between me and the clerk, it was probably justified.

Thankfully I still had all my crisp dollar bills in my shirt pocket, because despite having ridden four or five buses since landing, I’d never had to use them, since every fare reader was broken, or I was waved on because the bus was so late and crowded.

I drank about two gallons of water and Gatorade, and although only 5 p.m. I went to sleep. It was a bad night. My head pounded, my body cramped, I had a fever, and could never get comfortable, constantly flipping between dreams and hallucinations. Three times people pounded on my door, which I knew was real because I checked my phone to see the time, and took screenshots like any good journalist does, and also to help the police catch my killer. I watch a lot of Dateline.

It was probably more innocent though — people mistaking my room for their dealer’s room or for the place the party was. There were a lot of parties going on, the music from them bleeding through my walls, as well as the arguments around them. “You stole my pipe you fucking bitch!” was the only line I remember, because for feverish reasons I was on the speakers side, convinced that S had indeed stole his pipe. Which you simply don’t do to someone. Not without consequences.

The next morning, desperate to force a routine, I once again trekked to the McDonald’s, to get my coffee and the latest anti-Susan news. I felt a little better, my headache and fever were gone, but my body still felt like an overcooked noodle, and I ditched any plans for another walk. Anyways, I wasn’t in the mood to see more despair.

I did make it to Sunday mass, both for religious reasons but also to see a better side of Phoenix, and humanity. That did lift me a bit, to see functional families, together, with smiles on their faces, rather than grimaces of pain.

I spent the rest of the day in my room, only going out to get a lunch at the McDonald’s, and to stock up on Gatorade. This time I rode the bus rather than walked, and once again, didn’t get the chance to pay, since the fare readers were all broken.

At night my fever returned, as did the post-midnight door pounding, and when I woke up to an email reminding me of my flight to LA, which reminded me of my flight to Manila in four days, my heart sunk and I realized I was done. I didn’t want any more motel room illness days, any more feeling trapped, surrounded by the unfamiliar.

So I booked a late flight home, despite my flights to LA and Manila being non-refundable. Which meant two more bus rides to get to the airport, and maybe a chance to finally use the one day bus pass I’d downloaded, or stick in to the fare reader two crisp bills that still sat at the ready in my shirt pocket.

That last bus finally had a working scanner, and I gleefully paid, then sat in front of a young couple who spent the ride preparing a foil of perc 30s, which they had the decency to wait to smoke till getting off.

I wish I had something nicer to say about Phoenix, but it really sucked. I am sure people will point out I chose the worst part of the city to spend time in, but it’s a large chunk of Phoenix, adjacent to and including parts of downtown where lots of residents live.

While I feel awful for the broken people on the streets, am angry at our cruel society that values freedom, independence, and self-expression so much we give such little support, guidance, and fulfilling community to those with the least who need it the most, I feel worse for the residents of Phoenix who are trying their best to be decent people, who don’t do drugs, don’t panhandle, pay their taxes, try to pay their bus fares, play by the rules, and are hoping to find their tiny slice of the American Dream.

That dream still exists and the lower-income residential parts of Phoenix are a testimony to that, including a lot of Mexican-American immigrants who have so much relative to what they once had, who can hope to see their children grow up and do better than themselves.

But it also comes with neighborhoods now being locked down in response to the bedlam outside. Their bus stops pissed on, their streets littered with the detritus of drugs, their bathrooms locked, with the mirrors pulled out of them3.

None alone is a huge deal, but in aggregate it is depressing, bleak, and soul-sucking, that this downscale version of the American Dream comes with having to navigate around, and tolerate, an unnecessary tumult.

Having to navigate a Disney-like ride of human animatronics — empty of purpose or meaning, powered by drugs, and filled with despair.

I would like to say we are a better country than this. Richer, more empathetic, and less selfish, but I’m not so sure anymore. There is a profound emptiness in large parts of the US — a purposelessness, hopelessness, and spiritual vacuum, being filled by an addiction to the momentary relief, fleeting felicity, and the dulling numbness of weed, booze, and perc 30s.

A loneliness of the soul being tempered by a growing community of drugs, that well-to-do Americans have decided to ignore, presumably to let it play out in the “rougher” parts of town.

That’s a mistake, and it’s not fair to anyone involved. Not to the empty and broken, who are being allowed to slowly kill themselves one pill after the next, and certainly not to the residents of those neighborhoods, who shouldn’t have to be the only witness to it all.

PS: When I got home, I booked a less stressful trip to walk the Netherlands and Belgium. I leave next Thursday, and plan to walk from Amsterdam to Brussels, via Rotterdam and other places.

I need a break from the bleak, and these long walks through industrial Europe are my favorite.

‘Til next week!

It’s fascinating to listen to street users, especially those towards the bottom of the mental capacity range, regurgitate Mickey Mouse versions of modern therapy talk, which is centered with the idea of trauma. It’s become a very modern way for them to justify their behavior. It’s not my fault. It’s my past trauma speaking!

That they end up inventing trauma, when they already have plenty of real problems, shows how a lot of group therapy has now turned into an arms race of bad stuff.

The walks were made more strenuous because I carried my backpack, since I didn’t want to leave any valuables in my motel room. LOL.

It became a running bit to try and find a McDonald’s bathroom with a mirror. I never found one. They take them out because people either break them (for laughs), or scratch tag them, or spend so much time cleaning up in front of them (washing hair in sink, etc), that they’ve pulled them out altogether.

Well, this post was finally found by reddit and I've had to close the comments to only paying subscribers.

I don't really want to address their issues, because I'll let the piece speak for itself.

But the idea I unfairly targeted Phoenix by choosing the worst part of town entirely misses what I do. I don't ever stay in the touristy parts of town. I don't use cabs or cars. I walk and use public transportation, and I stay at the lowest cost motels I can find.

The part of Phoenix I stayed in, and walked, is a large part of Phoenix. It's not some weird anomaly. Just like the South Bronx is very much NYC, as is East LA, or Central Cleveland, or Northside Milwaukee, all of which I've stayed in.

Wow, just wow. I'm currently three weeks into a stay in Valencia, Spain. Over the course of three weeks I've seen maybe a half dozen homeless people and zero drug use. And no, we aren't in the nicest, touristy part of the city. It's very working class, but even the less "nice" neighborhoods are nothing like the hell hole you described.

It's shocking how much of America is broken.