If you stick to Ulaanbaatar’s center, as most visitors do, it wouldn’t strike you as that much different than any other post-Soviet city. It’s got the monumental plazas juxtaposed against newer glass towers. It’s got the Brezhnev-era apartment complexes, with their colossal tile motif-ed rectangular buildings. It’s got the wide boulevards, walled in by four-story apartment complexes, dotted with kiosks, and jammed with cars, trolleybuses, and pedestrians dressed against the cold. Well, it’s got only one boulevard really, with the perfect post-Soviet name, Peace Avenue, since Ulaanbaatar has only a little over a million and a half residents.

While that’s small, by most capital cities, it’s triple what it was when the Soviets were last here, or to be more precise last occupied it.

That sixty plus years of Soviet occupation, following around two hundred more of aggressive and non aggressive involvement is central to what Ulaanbaatar is, because Mongolians are a nomadic people not inclined to cluster together in one place, certainly not year round. Ulaanbaatar wouldn’t exist without the Soviets, which is contrary to the whole idea of being Mongolian, who have thousands of years of successfully living without private land, or the idea of permanent living, much less so tightly packed together.

It is, to use a currently overused phrase, a colonial construction, at both the physical and spiritual level, making Ulaanbaatar, like Bishkek, another city established by the Soviets to ‘tame the wild locals,’ a seeming contradiction. A mega city of nomads, with the mega not being about absolute population, but about percentages, and density.

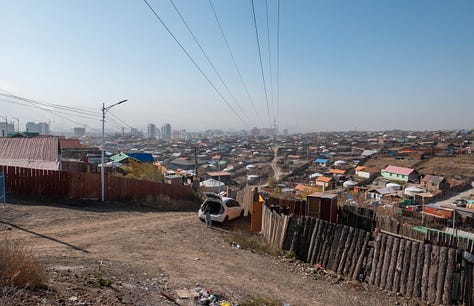

Almost half of Mongolians now live in or around Ulaanbaatar, and the majority do so in a manifestation of that contradiction, in a state between traditional and modern life. Where Ulaanbaatar really defines itself, and where it differs from all other world cities, is up in the treeless hills, mountains, and plains surrounding the city center. Where you find a serpentine network of pitted dirt roads, lined by wood and tin fences, behind which are one acre-ish sized plots.

Each of these plots is home to an extended family, living in a combination of concrete blocks homes and, as Mongolians have done for thousands of years, in tent like structures called Gers. The Gers can be assembled and disassembled in hours, but now rarely are, making these neighborhoods the original trailer parks, with the equivalent of immobile mobile homes up on cinder blocks.

These are the Ger districts, and they are out of sight of most wealthier residents, tourists, and the expats in the city center, despite making up over sixty percent of Ulaanbaatar by population, and more than that by land.

They are unplanned, unregulated, and self-built, the result of mass migration from the country side by Mongolians aspiring for the modern life they see on TV, in movies, and hear about from friends and family. Or at least to try their hand at it. It is also a migration driven by necessity, because while the traditional Mongolian life of herding is hard, it’s become much harder as Mongolia has opened up after gaining independence from the Soviets, exposing itself to a global marketplace that doesn’t value it, or understand it.