Some additional thoughts about Sofia

A golden brick road, Churches, Gypsy neighborhoods, and Malls.

(My first piece on Sofia is here: Walking Sofia)

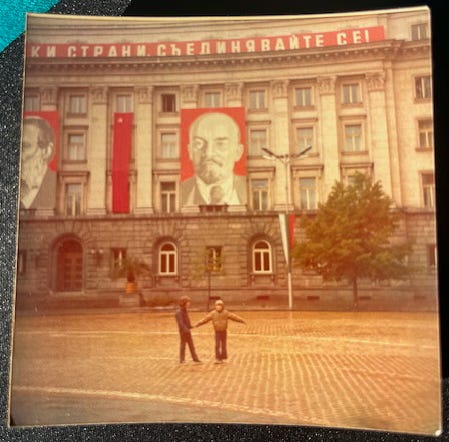

I’ve somehow lost one the favorite picture from my childhood. It was of me holding a pink balloon in an empty plaza beneath huge Communist posters. It was taken on May 2nd 1975 in Sofia; I’m sure of the date because the posters were for the May Day parade the day before, which we’d watched not sitting in the reviewing stands of the central plaza with the heavily meddled military types, but standing like everyone else about fifteen blocks away, jammed together as formation after formation of tanks, soldiers, and then children holding “peace flowers” marched by.

I also remember it because I’d turned ten three days earlier, a birthday we celebrated at a ski lodge in the hills above Sofia. It was an unintended gift of the professor that’d invited my father to speak at the University of Sofia. He had taken us not for my birthday, but to impress us with the wealth of Bulgaria. And impress me he did, because as we walked into the lodge there was a fireplace with an actual pig with an actual apple in its mouth roasting on a turning spit. Just like in the cartoons!

I do have two other pictures from that day, both fuzzy with age and fuzzy because they came from a crappy camera. My parents never cared for photography, since my mother was parsimonious to a fault, and my father convinced anything but the cheapest camera would be stolen.

I’ve written before (and here1) about my odd childhood of travel, something that clearly effects how I travel now, but of all our trips, the four months we spent behind the Iron Curtain probably impacted me the most, because it gave me an early and lifelong mistrust of “the official narrative.” What I saw in East Germany, Bulgaria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania, was so different from what the local governments claimed.

There was an obvious, large, and consequential class divide, with the elites (many of whom had been in the viewing stands the day before) having immense unchecked powers, and also access to a lot more stuff, including being able to go to dinner in ski lodges to eat roast pig2. There was also a lot of fear. Most people were scared to talk to us, including my father’s relatives, who would only discuss politics when we were alone, and even then, they whispered stuff into my parents’ ears.

We were also scared to talk, and monitored closely. Wherever we went, we had to check in at the local police station, handing over our passports until we left the city3.

Most of all, what struck me was how I was there4, and yet they couldn’t leave. Not only because of resources. Travel was tightly limited, with only a few high placed officials allowed to leave the country. Something that no amount of arguing could convince a ten year old made sense. You are forcing people to stay here? How in God’s name does that not mean this place is bad?

There is another picture from that trip I’ve lost. It is of me and my brother standing on a hiking path, and I’m posing holding something between my thumb and index finger for the camera. It was a small metal nut I’d found on the floor of a hotel bathroom in East Germany. I’d named it Nutty, and became determined to bring him to freedom, so I carried Nutty in my pocket for the remaining months. It had started out as the joke of a bored kid, but I got weirdly attached to Nutty, so much so that when I dropped him down the sink while washing him (yes, I washed Nutty), I was so distraught that I’d failed Nutty, that I spent hours fishing him out with a hook and string I made from a paperclip.