Walking Faroe Islands (part two)

Transcendent natural beauty in a nation that gets things done

(Part one is here: Walking Faroe Islands)

The natural beauty of the Faroe Islands is an embarrassment of riches, with so many splendid views, so many spectacular vistas, so many impossibly charming villages nestled around narrow harbors beneath cliffs, all of it decorated with sheep, waterfalls, and rainbows, that attempts to list the must-see “scenic spots” is a rather silly exercise that degrades the transcendence, but does send tourists off on mad dashes from island to island, check-list in hand.

The handful of other visitors on my improbable direct flight from Newburgh, NY to the Faroes all had some version of this list, as well as a tour-guided heavy itineraries, which I didn’t, and so I began to feel maybe I was wasting an opportunity, flying in too blind, too ignorant, and I was going to miss out on sites I needed to see.

By the end of my first few days here, and after my first walk out of Tórshavn and across Streymoy Island, I knew that feeling was silly, because there’s no walk in the Faroes that isn’t rewarding, and if you have the luxury of time, then it’s far more relaxing, fulfilling, and enlightening to take a scattershot approach of what to do in the Faroes, which is what I did after my sore back healed.

So for the last ten days I’ve woken up early, looked at the bus schedules, spent fifteen minutes on OpenStreetMaps, and then somewhat randomly chose a destination, and after an hour and half bus ride, where the views from the windows alone are worth the ticket price, spent the day hiking along small roads, trails, and pathways, before returning for an evening in Tórshavn.

What you see when you do that is how extensive, integral, and essential to the world-view of the Faroese the landscape they live in is. It has shaped them, and they in turn have transformed eighteen seemingly adversarial (geographically and meteorologically) islands into a nation1 that works.

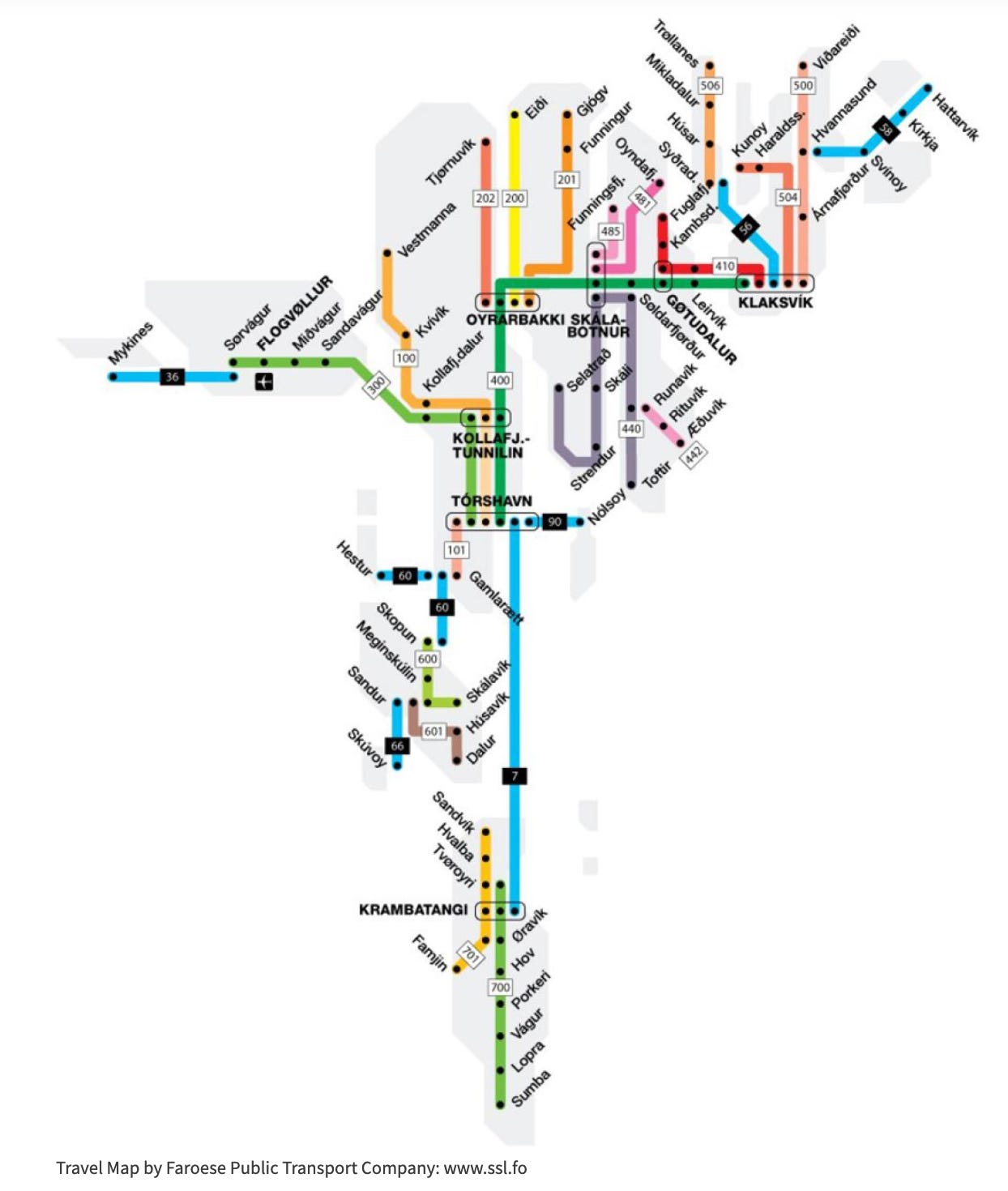

The public bus/ferry system, which enabled my wing-it approach, is evidence to the Faroese competence: A network that allows you to get to almost all of the places people live, no matter how remote, on islands scattered over five hundred square miles, without a car.

Connecting all these islands, each a layered undulating vertiginous mound of eighty- million-year-old lava, separated by cold tempestuous seas, isn’t an easy task, but the Faroese have done it. The public transport map, which looks like the London metro system was shattered by a meteor, the bits falling like pick-up-sticks, and nobody bothered to fix them, highlights how skillful an accomplishment it is2.

The system is great for tourists but that’s not the reason it exists, or who uses it most. It’s built for locals, mostly school children, and riding a bus, especially right before school starts, and right after it ends, means being surrounded by chattering teens heading to the mall3, or younger kids getting off at solitary bus shelters, bounding off alone into the distant tiny cluster of homes. Like in most of the rest of the world, other than the US, children in the Faroe Islands are surprisingly independent, navigating the world without a parent hovering nearby.

By the end of my first week here I began to agree with my cab driver from the first hour after I arrived, which is the human built infrastructure is as, if not more, impressive than the natural beauty, and while I doubt few would want a guided tour of it, you could easily compile a list of the top ten Faroese engineering marvels.

Near the top would be the conspicuous projects, like the three-mile sub-sea tunnel with a round-about in it, since it connects three different islands. But it’s the more mundane projects that impressed me most, such as the power lines strung improbably high, arching across fjords, cliffs, and mountains, that keep all the islands electrified, and the network of cell towers, found on every fogged-in peak that looks impossible to reach, much less build something on, that mean no matter where you are you always have five bars.

The Faroe Islands is super efficient and functional, and given the geography, climate, and location, that’s a testimony to human adaptability, and more particularly the competence of the Faroese.

The infrastructure cost, shared by all, including the twenty-five thousand who live in Tórshavn, is a testimony to Faroese egalitarianism, since every citizen, no matter where they choose to live, has the resources to thrive. That means de-ruralization, the pull towards clustering in the“big” city, isn’t being accelerated in the Faroe Islands by policy as it is in other parts of the world, and so someone whose family has lived for over seven-hundred years in the tiny town of Kunoy, forty miles and three islands away from Tórshavn, can continue to live there, without a crippling degradation in basic services.

That egalitarianism also shows up in the data economists and policy types focus on, where the Faroe Islands is deemed by those on the left as having a tax system that’s “the best on the earth”, which contributes to them also having the lowest income inequality in the world, at least according to the favorite inequality metric of economists.

You don’t need data to see how how integral a “we are all in this together” communal-ism is to Faroese national pride. Walking around, talking to people, you’re struck by how few differences there are, in wealth, appearance, and attitude. Everyone seems firmly entrenched in the working middle class, with none of the extremes found in the rest of the world. Gone are the pockets of debilitating poverty, as well as the gated enclaves of ostentatious wealth. Also gone, is the the “Hey, look at me, look how different I am” style, attitude, and ideology that dominates so much of the West, especially the US.

Everyone is generally the same, and that uniformity, which others might see as verging on creepy, I saw as refreshing, because it isn’t built entirely around race or ethnicity. There are minorities in the Faroes, a smattering of of Asians (Thai, Filipinos, and Chinese), Africans (Ghana, Nigeria, and Uganda), and Eastern Europeans (Bosnians, Albanians, Serbians), who have come for some combination of work, marriage, study, and sports (handball), and then quickly integrated themselves into Faroese culture, both by learning the language, and by becoming contributing members to the nation. I saw the same at the small Catholic church4, where at least half the congregation are immigrants, most now citizens.

That last bit, learning the language and becoming a contributing citizen, is an unwritten requirement to being accepted in the Faroes, enforced by the same unifying forces that percolates underneath any long lived small-town culture: Join the tribe, or leave.

None of the immigrants I talked to (about thirty) had anything negative to say about their experience in the Faroes, unless it had to do with the dreary weather, the boredom, and the dark winters, which is a complaint I heard a version of from everyone, no matter how many generations their ancestors had been there.

That physical and cultural homogeneity is the only reason I discovered there was an international football match happening in Tórshavn , when on a Friday night I spotted four swarthy athletic dudes in matching monochromatic track suits, with North Macedonia patches, in the popular Irish pub.

They stuck out, especially since there weren’t any cruise ships, or visiting military ships, docked at the harbor fifteen yards away5, which brought friendly questions from the regulars, as well as from the bartender, who was originally from Serbia.

Of course I had to go to the Faroe Islands versus North Macedonia match, one of the oddest pairings possible in Europe, to see who would be crowned champion of the obscure mountainous nation cup, but mostly because there isn’t a lot else to do on a Saturday in Tórshavn, other than go for a hike, and my back was still sore.

While the game wasn’t a sell out (had it been, one eighth of the country would have been there) the crowd was enthusiastic, despite the Faroes being a world soccer punching bag6 , the team you attempt to run up the score against for goal differential tie-breaking reasons. Given the size of the country, and that most of the players have day jobs, their bottom basement position isn’t surprising, but they continue to play on, as an independent nation, another mark of their national pride.

I’d intended to maximize the absurdity factor by sitting with whatever North Macedonian fans I could find, but while walking towards them (a group of maybe ten sitting near the teams bench, all draped in flags), I passed by the Faroes cheering section and had to stay there, because as they say, “when in the Faroe Islands, do as the Faroe Islanders do.”

That “adapting to the local cultural norms” included drinking lots of beer at the game, then heading to the local dive bar (Tórshøll) to keep the “Yeah, we tied North Macedonia!” party going. I stopped at doing shot after shot7 of the locally popular Fisk, described by a visiting Canadian as “Fisherman's Friend cough drops in liquor form.”

Turning down shots bought by very drunk men became a regular weekend thing for me, because while the Faroese don’t go out to bars much, when they do go, they go very hard and become even more friendly and charitable. That included the seventy year old Ríkaldur (I think that was his name), a “sailor,” who boated into Tórshavn twice a month from Svinoy, an island with at most a hundred people, where his relatives have lived “for forever,” who thought that my turning down a free drink meant I was mentally ill.

While they drink a lot, what the Faroese don’t do very much of is hike, since most don’t see the point. While they recognize the beauty of their country, they’re always surrounded by it and don’t feel the urge to complete a scenic checklist.

They approach nature very differently than tourists like me, happy to exist in it and be part of it, since it’s part of who they are, rather than something to visit with the intent of having an experience. That contrast, between nature being something you're part of, for the sake of simply being part of it, as opposed to something to go into to marvel at, and then document your marveling at it, was especially stark on my walks in the Faroes, which began to explain why I felt so much more fulfilled on my seemingly goal-less hikes.

Then, five miles into a rather arduous walks, when I was resting at a particularly scenic spot, enjoying the view, the sheep, and the accomplishment, a car sped up, came to a stop with a shower of dust, the doors flung open, and five people in shiny hiking gear hopped out, snapped photos, and then they jumped back into the car, and drove on, coating me, and the few remaining sheep, in another cloud of exhaust and dust.

Watching scenes like that, as well as what Martin had said early in the week about not needing to ever take a picture when hiking, started making me feel ludicrous for carrying along my camera and snapping so many photos.

That shouldn’t be the point of going into nature, especially since the photos don’t capture the majesty of the scenes, whose impressiveness and scope is impossible to convey in a single frozen frame. So I tried switching to video, which at least gives a better sense of the vastness of the beauty, but even that falls far short.

As I’ve written before, after my walk along England’s south coast, nature is the most foundational art form, in the sense of Walter Benjamin’s concept of aura as defined in his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility,”

"even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: Its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be."

Natural beauty is pure aura, pure “presence in time and space,” pure “unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” You can’t reproduce nature, certainly not with photography, and not even with videos, since both fail to capture the sublime, majestic, and “the aura” I saw and felt during my walks.

Not only is nature perhaps the purest form of art, it also, like in the Faroes, rises to the meaning-making level, with place imbued with a transcendent, religious, form of importance, providing the people living there with a sense of metaphysical purpose.

The Faroe Islands is special, all the residents say that. It’s unique, all the tourists say that, but not only at a material descriptive level, but also at a spiritual level, which is perhaps why so many young people I met there have no intentions of leaving, despite a lot of obvious economic reasons they might want to.

I started asking every Faroese I met if they intended to stay (all said they did), and how many members of their high school graduating class were still in the country, and the answers were all about ninety percent. While most do go to Denmark to study, the majority return, after a few years, or as they get older and realize they miss their home.

I was initially surprised by that answer, but the longer I stayed, the more I understood it. The Faroe Islands, to get corny and cliched, really is a magical place.

As Ríkaldur, the drunk sailor from Svinoy, said to me when I asked him if he’d ever thought of leaving, after looking at me like he was now sure I was completely off, “Why da hell would I go and do that?”

(I’m trying to keep a few more posts free — so please, if you can, subscribe, since when I paywall them I get way more paid subscriptions, and I’d rather not do that!)

Finally nailing down rough dates (give or take a few days) for my upcoming Asian trip:

Oct 3rd - 7th: Seoul (getting over jet lag and hanging in LP bars)

Oct 7th - 21st: Vientiane and maybe another Laotian city

Oct 22 - Nov 8th: Phnom Penh Cambodia

Nov 9th- Nov 18th: Walking Japans southern coast, from Kumamoto to Fukuoka, then taking a ferry to Busan Korea.

Nov 19th - 24th: Busan/Seoul

As always, if you are in the area, I would love a walking companion for a day, or a drinking buddy for a night. Or both!

If you are around, then please reach out to me in the comments, or via email.

Also, please considering hitting the paid subscription button, so that I can keep more of these posts free!

Until next week!

Yes, Faroe Islands is not exactly an independent nation. It is a territory of Denmark, but one with a great deal of sovereignty. Denmark does support the Faroes economically, sending roughly 1,500 per person in aid, but the Faroese also runs a current account surplus, and honestly might be better off without the aid, and the obligations it brings.

The website also has one of the best photos I’ve ever seen, since it perfectly captures the experience of taking buses across the Faroes.

While their team might suck (understandably), Tórsvøllur stadium is beautiful. Another engineering marvel that senselessly integrates into Tórshavn and it’s austere backdrop.

When you are in Tórshavn you can tell, without looking at the harbor, if there are cruise ships or military vessels docked there, because their presence changes the dynamics of the city. Hundreds of visitors will do that to a town of only 20,000. Think of fleet week in NYC, but on a much higher percentage scale.

One of my guardrails in life is never doing shots. Consequently I’ve now turned down more drinks across the world by very drunk old men than I can count.

Welp, now I have a new place on my bucket list.

Chris, I'm glad to read of your enthusiasm for the Faroes, because if you'd panned it, I think I'd have to reexamine everything else you've written. I'm not sure I've read of anybody who doesn't come away enchanted by those islands.

Since Iceland has become so trendy, some might want to know that there's a way in and out of the Faroes other than flying via Denmark. Seasonally, the Smyril Line runs an overnight ferry from Seyðisfjörður, on Iceland's east coast. It's a great trip.

Cheers!