The Divine Engineer of Ancient Sichuan

To understand the new China, one must understand how it has preserved and revived elements of the old

(I met Jonah in Shanghai, and he was kind enough to walk with me for a day. He was the perfect companion because he is both a PhD student of Chinese and Eastern Philosophy. My piece on Shanghai was influenced by his thoughts, especially my use of Plato’s Republic. So I was glad when he reached out and offered to write a piece, and especially happy when I read it and saw that in it he politely corrected, or amended, my rather simplistic views.

Jonah has his own substack, which you can find here: Arriving Yesterday.)

The first thing one notices about Chengdu, capital of the western Chinese province of Sichuan, is how eager the city is to lean into its theme: the pandas. Smiling pandas peek out of storefront windows, beckoning in tourists to buy panda-themed keychains and fridge magnets. Children run around in black-eared headbands, threading between scooters parked in long rows on the sidewalk. In front of the Lego store in Chengdu’s branch of Taikoo Li, one of China’s premier chain malls, there stands a Lego brick model of a giant panda, larger than life, avatar of the cutesy aesthetic and the material abundance that so define the urban landscape of the new China of the 21st century.

Of course, this new China is just the latest in a succession of “new Chinas” in recent history, from the new China of a national republic to the new China of socialism with Chinese characteristics. But it is a China which outside observers, particularly those better acquainted with its predecessors of previous decades, are liable to find bewildering. In the new China, sleek modern office buildings box in sunken cobbled streets. In the new China, villagers pitch in for group orders of produce and medicine from an online shop. In the new China, street vendors deep-frying potatoes and tofu in an open vat of oil have you scan a QR code to pay with your phone. I’ve only seen one beggar in China since moving to Shanghai last August; he was in Chengdu, sitting on a blanket in front of an entrance to the subway station, head bowed over his personal QR code for WeChat Pay.

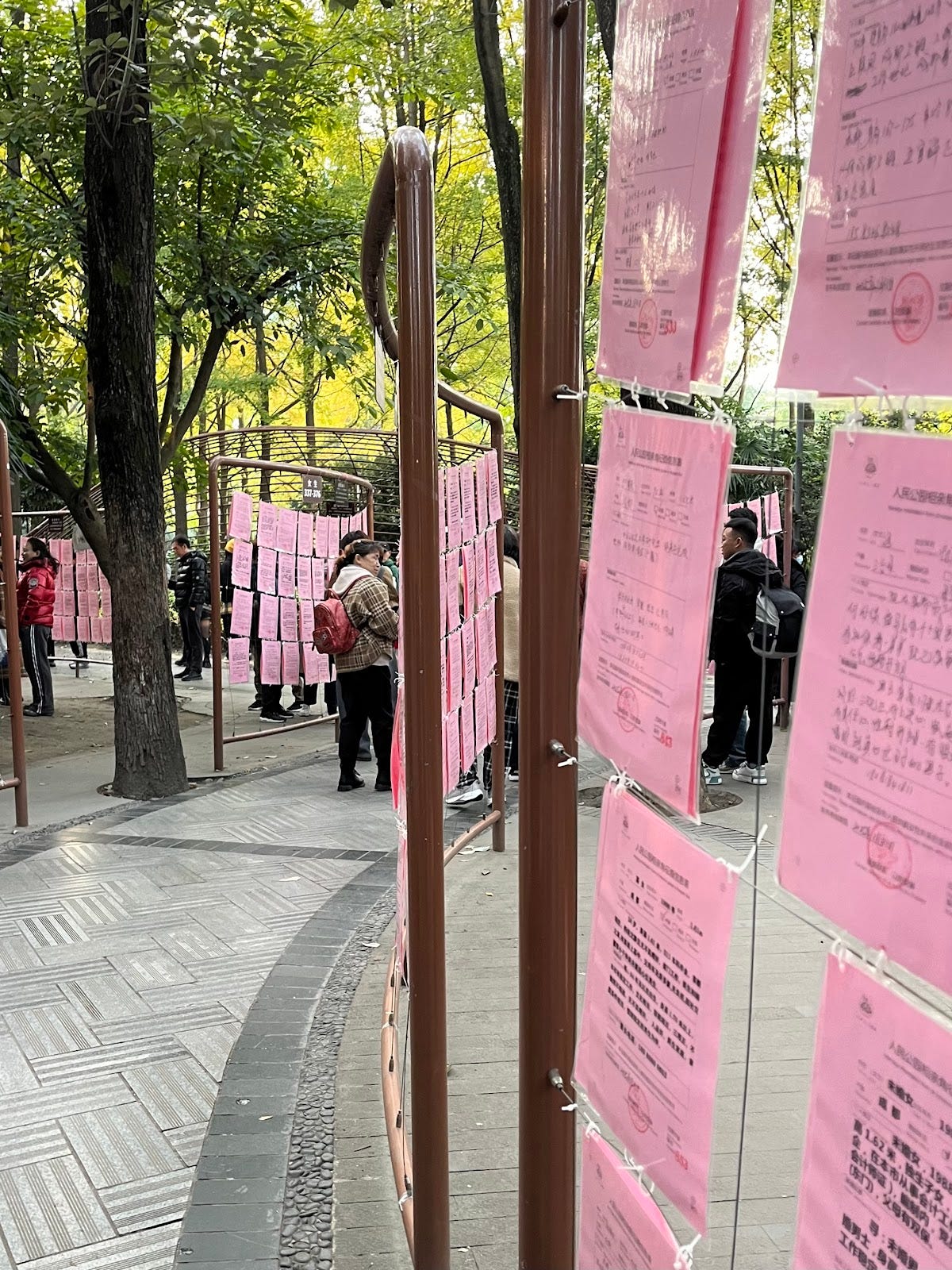

I traveled to Chengdu with friends for American Thanksgiving. We saw the giant pandas (the real ones) at the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding. We walked through a park with a bustling marriage market, where anxious parents have covered the fences with profiles of their progeny—education level, height, year of birth, etc.—and their requirements for a commensurate match. In lieu of turkey we had hot pot. We saw the new China, how it has found expression further inland, in this provincial city of 21 million, beyond the commercial hub of Shanghai and the heart of power in Beijing. But northwest of the city, by the town of Dujiangyan, there stands a monument to that other China, the old China—not the China of the skyscrapers and the luxury malls, of the happy mascots and the seamless, screen-mediated daily life, but the China of awesome empire and ancient gods.

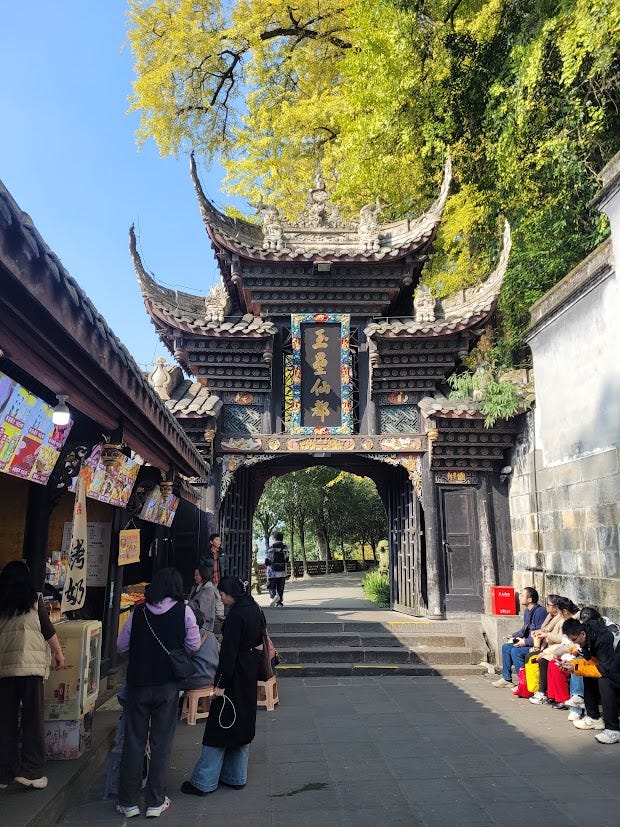

I am referring to the Dujiangyan ancient irrigation system, built around 256 BCE in what was then the western frontier of the Chinese world. We took the bus to the Dujiangyan historic site up dusty hills overshadowing Chengdu’s gleaming corporate plazas. The entrance gate stands at the height of a valley, leading into a wooden tea-house hugging the hillside. Down the stairs and further on the trail, past a cluster of Buddhist temple buildings, one finds the first major draw of Dujiangyan: the Two Kings’ Temple.

The main hall of the temple houses an idol of the local hero-turned-deity Li Bing, before which stands an offering table covered with oranges (a staple of folk religious worship) and various packaged snacks and soft drinks with sodium levels and calorie counts of which the historical Li Bing could not have dreamt. Chinese visitors burn incense sticks and bow to the god before passing on. The rear hall is dedicated to Erlang, another local hero said to be Li Bing’s son—though here, already, the story of this Li Bing shows itself to be obscure.

There is no note of a son of Li Bing in the historical record; even the official Dujiangyan historic site audio guide admits that the townspeople likely invented the Erlang figure, or else came to associate an existing figure with Li Bing, since they thought a man of virtue such as him would have passed on his virtue to further generations. As for Li Bing himself, two main stories of the basis for his apotheosis have come down to us.

The first story goes like this:

Li Bing, a warrior from the north who had taken command of the state of Shu, gave his daughters in marriage to the god of the river Min. The river god refused to join Li Bing in a wedding toast, so the offended father-in-law fought him in a duel. With the aid of his attendants, Li Bing defeated the god.

From that point on, the Min no longer troubled the people with demands for sacrifice. Today, the “Two Kings’ Temple” at Dujiangyan memorializes Li Bing’s triumph over the capricious divinity who had persecuted the people of ancient Shu with wrathful floods.

In the second story our hero’s achievements are more mundane, but no less impressive:

Li Bing, a statesman from the state of Qin in the north appointed as military governor of the conquered state of Shu, built an island of piled stone in the middle of the river Min, dividing the waterflow into “inner” and “outer” streams. Shaped like the mouth of a fish, a levee at the upstream end of the island would redirect part of the waterflow down the new “inner river” and through another artificial channel carved into the mountainside. This channel would take the waters further east, towards Chengdu, where they would irrigate the rice paddies of the plain rather than overflowing the natural riverbank. (A weir at the downstream end of the island would allow excess water to flow back into the original, “outer” river.)

From that point on, the people of Shu enjoyed agricultural prosperity and relief from floods. Today, the “fish’s mouth” island at Dujiangyan testifies to Li Bing’s triumph over the wild forces of nature which had inconvenienced the people of Shu with destructive floods.

But even to separate these stories as I did just now is arguably misleading; the temple to Li Bing at Dujiangyan presents him as both a brave hero and a brilliant engineer, and the historical record counts his stage-managed triumph over the river god among his tactical achievements.

According to historian Steven F. Sage (reporting a story preserved in Li Daoyuan’s Commentary on the Water Classic), the shrewd governor contained local superstition by staging a “duel” between two bulls which he claimed represented the god and himself. His attendants slew the unlucky bull, and with the god of the Min pacified, the practice of human sacrifice to the river god came to an end. Li Bing, as governor, then went about constructing the irrigation system, manifesting in fact the defeat of the river he had already symbolically effected as warrior.1

In the dual story of Li Bing, at once a hero and a statesman, a deity and a public servant, the natural and the supernatural coexist. That his actual accomplishment was an engineering project, and his struggle with the divine openly fraudulent, has done nothing to damage his cult; on the contrary, the current Two Kings’ Temple was only built in the Song dynasty, over a thousand years after Li Bing’s lifetime, by a latter-day emperor who admired his methods of flood control.2

Further legends grew up around the Li Bing and Erlang figures: off the eastern bank of the inner river stand the Dragon-Taming Temple, which honours the father-son duo for subduing a river dragon who in this version of the story takes responsibility from the god of the Min for the river's routine flooding. With the dragon defeated, work on the irrigation system could commence.

However the story goes, Li Bing did good for the people of Shu, which became Sichuan, so they decided to worship him. He needed descendants, so they gave him a son in Erlang. And in this, the people and the powers that be were in agreement.

After leaving the temple grounds, we crossed a suspension bridge spanning the inner river to get to Li Bing's island. Peering out over the railing to admire the fish's mouth structure, I saw a plush red panda toy washed up on the rocks. But aside from that intrusion by this latter-day local idol, the ancient governor's handiwork appears otherwise untouched by time.

Li Bing is not even the most famous hydraulic engineer of Chinese lore, however. That distinctive honour goes to the sage-king Yu of deep antiquity, who (tradition holds) worked tirelessly for years to contain the floodwaters that made the ancient Chinese plain unlivable.

Yu the Great is celebrated as a model ruler in the early works of Confucian philosophy. The Mencius (one of the cornerstone of the Confucian canon) tells us that Yu (as minister to his predecessor, the sage-king Shun) spent eight years abroad dredging and redirecting the rivers of the world: “Three times he passed the gate of his home but did not enter. Even if he wanted to farm, would he have been able to?”3

It's not that Yu wanted to avoid his family; it’s just that his compassion for the people meant that he could do nothing other than to try to tame the waters. Indeed, the Mencius ascribes to Yu an almost supernatural capacity to sympathize with the common man: “Yu thought that if there were anyone in the world who drowned, it was as if he had drowned them himself.”4 He and the other sage-kings of old felt that they must “labor with their hearts” to guide and benefit the commoners who “labor with their strength”.5

Unlike their Homeric counterparts, like your Heracles or Achilles, the great heroes of Chinese tradition were not known primarily for slaying beasts and besting rivals. Rather, they were celebrated first and foremost for their service to the people. Li Bing was just another hero-minister in the tradition of Yu the Great, and as such, in the distinctive manner of Chinese tradition, whereby conscientious public servants, not strongmen, are those marked out for deification, he too was celebrated in history and worshiped at temples.6 In traditional China, a middle manager could become a god.

In his essay on Shanghai published in this space last November, Chris Arnade suggested that the CCP of the 21st century—the ruling elite of the new China—has modeled itself after the guardian class of Plato’s Republic. It’s certainly true that this regime has taken on responsibility for ambitious, top-down state management, making the comparison to Plato’s guardians an apposite one. But the explicit model for the new CCP comes rather from intellectual sources closer to home: Xi Jinping is fond of quoting Confucius, and even referenced the legend of Yu the Great on a visit to flood-ravaged Anhui Province in 2020. Under President Xi’s leadership, the government of the PRC has made efforts to rehabilitate the Confucian tradition and reestablish the moral authority which that tradition lost in the ideological upheavals of the 20th century. Mao’s portrait may still loom over Beijing from the entrance to the Forbidden City, but I’ve seen the image of Confucius on university campuses, at historic sites, in 360-surround-view cinematic experiences at new educational centres, even, throughout the country.

In Confucian political thought, the true king gains his legitimacy from heading a government for the people (though by no means by and of the people); throughout the Mencius, the titular Confucian thinker urges the princelings of his day to extend their compassion to their common subjects and institute “benevolent governance”. It is no surprise, then, that the heroes of Chinese culture are men like Li Bing, men known more for their public works than for their private deeds. The 21st-century CCP wants to position itself as a defender of the traditional Chinese political ideal, as a party of benevolent governance in the Mencian mold, that, like the ancient hero-engineer-warrior-governor Li Bing, benefits the people with feats of engineering, though in this case the engineering in question is as often social as it is physical.

I said that in Chengdu I saw the “new China”. But of course, this newest China is built over all the older Chinas that preceded it, concrete over cobblestone, wi-fi networks interfering with the primordial patterns of yin and yang. In the city, in the courtyards of technicolor shopping centers occupied by KTVs and barbecue chains, one finds entertainers dressed as folk heroes like Sun Wukong (the Monkey King of Journey to the West). And out in the country, behind turnstiles moved only by scanning a QR code, one finds the old hunting grounds of dragons and the temples of the heroes who triumphed over them.

The supernatural denizens of the river Min may have lost their place in the popular consciousness to the pandas of Chengdu. But if the name of the “Dragon-Taming Temple” is an accurate one, then Li Bing and Erlang's river dragon, at least, was never finally vanquished: he was only tamed, like so many other figures of Chinese lore, for service in the ideological projects of his mortal masters. To understand the present PRC regime, one must understand the many Chinas it has inherited, the intellectual heritage it has now explicitly revived, having never fully suppressed, and the ideal of a ruler whose claim to fame is that he controlled the waters to serve the people.

(PS: So, my break it seems will only last a few weeks, since my daughter’s health has returned to normal, and I found myself with an uncancelled ticket to Asia and a desire to see China again, so I just booked a trip to Beijing and Seoul starting February 14.

I will be in Beijing from then to the 20th, and in Seoul from the 20th to the 24th.

I will be hosting an open bar on Friday night, Feb 21st, at Woodstock Vinyl bar in in Sillim-ro. I’ve written about this LP bar before, and hope some of you can make it that evening to sit, chat, and request obscure rock songs from Mr Moon.

As I mentioned before, I am still planning to be in Washington, D.C. on Feb 27th, and giving a talk in an Arlington Virginia McDonald’s from 3 p.m. to 4:30 p.m ( 6020 Rose Hill Dr, Alexandria), followed by a 5:30 p.m. happy hour at local Mexican restaurant (Helena's 5735 Telegraph Rd, Alexandria, VA).

Until then, have a great few weeks — Chris)

Steven F. Sage, Ancient Sichuan and the Unification of China, p. 150-151.

Heping Liu, “Picturing Yu Controlling the Flood: Technology, Ecology, and Emperorship in Northern Song China” in Cultures of Knowledge, p. 115-116.

The passage from which this quote is taken describes in vivid detail the impossible conditions of the world in deep antiquity and the efforts of the various sage-kings and their ministers to alleviate those conditions:

“In the time of Yao, the world was still unsettled. Great waters overflowed their banks, spreading throughout the world. Plants and trees overgrew everything, and animals multiplied in great numbers. The five types of grain did not ripen. Animals harried people. Paths made by the tracks of animals crossed the Central States. Yao alone was anxious about this, so he promoted Shun to rule over it. Shun directed his minister Yi to take charge of fire-clearing. Yi burned the overgrown mountain fields. Only after the animals fled did Yu channel the Nine Rivers, clear the Ji and the Ta rivers to guide them into the sea, dredge the Ru and Han rivers, dredge the Huai and Si and guide them into the Yangtze. Only then were the Central States able to eat. During this time, Yu spent eight years away from home.

Bryan W. Van Norden (trans.), Mengzi 3A4.7, p. 122.

Van Norden (trans.), Mengzi 4B29.4, p.165.

Van Norden, Mengzi 3A4.6, p. 122.

See Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4: Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3: Civil Engineering and Nautics, p. 247-250, for the connection between the figures of Yu and Li Bing.

great juxtaposition of old and new; thank you

Great pictures! When I went to the 5A irrigation project, we entered from the bottom and walked up. It's fascinating to realize that without Li Bing and his taming of the Minjiang River, a consolidated China might never have happened, and certainly wouldn't have happened for the Qin.