Not Walking Chicago

A week stuck in a McDonald's, thinking about America

I’m writing this from a McDonald’s in Northern Indiana, blasting top forty (oh-ee, Makeba, Makeba ma qué bella, Can I get a “Ooh-ee”? Makeba, Makes my body dance for you) as it snows another four inches outside. It wasn’t supposed to snow today, but four inches of snow when it wasn’t supposed to snow has been the normal for the last week.

The high today is expected to be five, which with wind gusts means a Feel-Like of minus something absurd. Younger me, raised in the sunny orange groves of Florida, hyped up on physics, used to believe Feel-Like was a marketing scam of the Big Industrial Weather Complex, like naming winter storms as if they deserved hurricane-like status. Then I moved north and all my Big Weather conspiracy theories were shorn away, like the cocoon of heat around your body by a January wind.

I've adopted this McDonald's, a mile walk from my room, and so I know everyone else currently in the dining room. That includes the four men, each in their respective nests, who all live precarious but regimented lives devoted to drugs, either mandated or illegal.

Going around the room, starting from my immediate left: the young black man (Money) swaddled in layers of Goodwill camo, slumped in his corner table watching YouTube videos while sucking down orange soda courtesy of the dangerously thin employee whose owl-like glasses are somehow always fogged up.

Then there is the odd couple at their usual booth—the younger sweet-voiced Vietnamese middle-aged man (Binh) with his flamboyant found fashion (today he's wearing a shaggy '70s-style white fur vest over a blue bathrobe; yesterday it was a cowboy theme, complete with fur Stetson) and his seventy-plus friend (I call him Carlos, because he looks like my recently deceased brother of the same name), with tufted hair and painted fingernails ("That Korean woman keeps painting my nails," as if everyone knows that Korean woman and her quest to color the itinerant male population). Binh and Carlos pass the morning amusing each other while watching TV, or playing cards, and whenever Binh says something absurd, which he does often, usually about aliens, Carlos looks over at me, rolling his eyes. He might live in a tent in the woods like Binh, he might be sporting a coat with a rip exposing an inner fluff that trails him like streams of smoke, but he's still firmly sane.

Completing the morning quartet is Terrance, the quietest member, who doesn’t socialize with the other three and spends hours hardly moving, a hotel Bible opened before him, the page rarely changing. His drink of choice, black coffee, is also courtesy of an employee, but a different one, an older Black woman who can most politely be described as round-shaped.

The other regulars live more traditional lives. There is the pre-teen daughter of an employee who, when school is out, sits for the entire morning shift in a corner booth, dressed in going-out-of-the-house PJs, watching videos or playing on her phone while her mom works. There are DoorDash delivery guys who cluster around the Pick Up counter, trying to leverage their wages with FanDuel. The contractor with his three screens (laptop, phone, tablet) snaking into the outlet, contracting more jobs. The well-put-together elderly woman with her book and her brand-new leopard-skin pill-box hat, who I had to tell how pretty she looked.

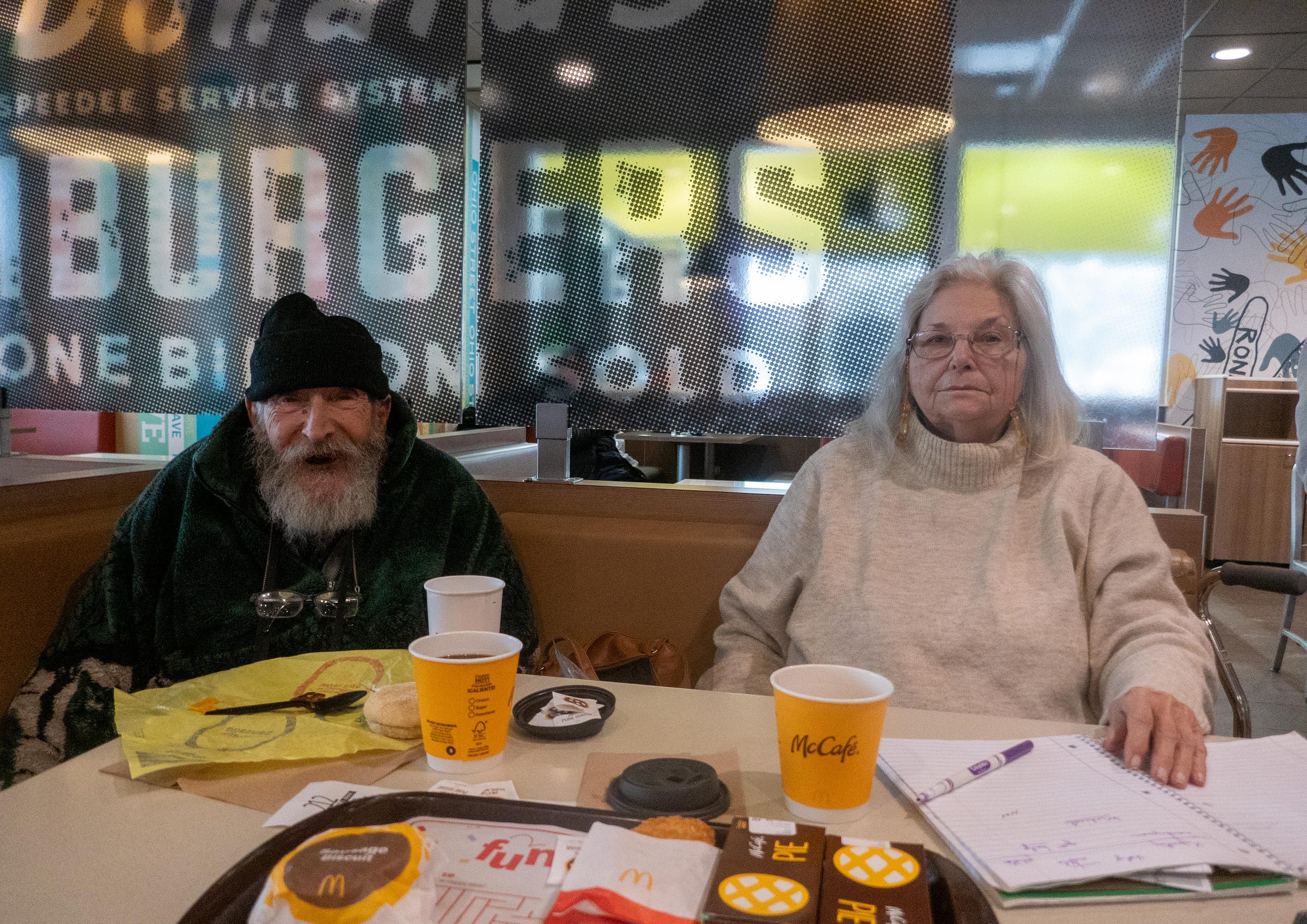

Then there is Scott and Judith (cover photo) who come each morning in their 2003 PT Cruiser, devoid of both bumpers, to “have a breakfast outside of the house.”

Scott lives with Judith, a now twenty-five-year arrangement that began in a coffee shop. “I had to get to work, and it was busy, the restaurant was busy, and they didn’t have a seat for me, so they asked him if I could share his table. A very, very, very appropriate moment. He was a total stranger but it was serendipitous because he needed a home then and I had an extra room and so now here we are and I promised him two years ago I wouldn’t let him go to a nursing facility, so he could take care of his dog, his birds, and I would take him out for breakfast every day, so that’s why you see us here every morning.”

Judith passes her time reading and writing in a notebook, mostly her memoirs, which she outlined to me over a few hours, edited down to remove the detours someone in their late eighties is prone to.

“I was born on a farm in the little town of Somerville. These were not big farms. They were just a bunch of little farms, and well, we lived on twenty acres. There was nothing there, not even a restaurant. No McDonald’s. You couldn’t even go get an ice cream cone anywhere or Coke. We lived in three rooms without running water. What would you do? Well, you have to go get a job. And only there wasn’t any jobs around, because farmers do it themselves and they don’t pay much, so I had to leave and get a job and so I went to college, the community college because that is all we had, and oh, I just thought that library was heaven and wanted to read and learn and I graduated magna cum laude and became a teacher and so I recovered pretty good for a farm girl because once you see a library like that you have to do that. So I been teaching and reading all my life and now my house, and I admit it’s got an excessive amount of books and art, but I don’t want anyone to come in because everyone wants to throw away all of my books, including my Bible that has a Civil War letter in it. I took that old Bible in to get my driver’s license because I lost my birth certificate to show them I was born here, because it’s got all the births in my family written down in it, one after the other, like a family tree. The first one is the relative who grew up to fight in the Civil War, and then there is my birth, and I figured they could use that to give me a driver’s license but they didn’t, so that’s why Scott drives us.”1

I didn’t come to Chicago to spend it sitting in a McDonald’s. I wanted to walk the city, especially its Southern parts, before departing for Minneapolis, Duluth, then points further West, but the weather system that’s descended on the entire U.S. has meant walking has been close to impossible, less because of the extreme colds, and more because of sidewalks covered with snow and ice deposited by plows, and leaving for warmer climes limited.

So for the last week I’ve been in this McDonald’s in the mornings, taking short walks when I can, and then hanging during the evenings in a local dive bar with a different set of regulars devoted to a different drug, eating tavern-style pizza, watching sports, immersed every few nights in the exhilarating and uplifting spectacle of local Karaoke2, when you see how talented “normal” people can be—like the unassuming twenty-year-old in his trucker cap, who works construction, that belts out a stunning version of Dwight Yoakam’s “Try Not to Look So Pretty” or the elderly black man in monochromatic bright red (jeans, jacket, cap, shoes, socks, glasses, earrings, and wallet) who goes “old school” with Teddy Pendergrass’s “Close the Door” or the shy Hispanic woman who, despite her meekness, pulls off a close to perfect version of Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You.”

I love this bar, which would rightfully be offended by being called a dive bar because it doesn’t consider itself to be beneath anything else. It fits my rule of staying away from any bar that claims it is a dive — The best bars, with dive-y qualities (unpretentious, inexpensive, locally owned, familiar) don’t know they are dive bars and don’t curate that image. They are only self-aware to the extent it means serving their regulars, on their terms, which means being warm, with a side of complicated and messy, like life.

They are not entirely without some self-recognition though, and despite their desire to be as respectable as possible they go into battle mode on crowded nights when bouncers materialize out of the dank carrying boxes of plastic cups to switch entire bar’s stock from glass. When I laughed, the bartender said, ‘It’s for the better. People can start throwing stuff when it gets a little heated.’

I’ve only seen incipient heat once. When the young man with four children from four different baby mamas who, after putting a few hundred on a Bears overtime win, which he lost, turned sour, and then was accused by the lady he was trying to convince to be his fifth baby mama, of stealing her phone, which pulled in nearby males on each side of the issue, bringing the whole scene dangerously close to a critical chain reaction explosive mass.

He hadn’t swiped her phone, it was all a shot-fueled gambling-loss misunderstanding defused by good Samaritans sipping jack and cokes, but had it escalated the bouncers stood ready to control the situation, with plastic the only possible weapon, unless someone had smuggled in a weapon through the bouncerless side door, which is always a risk I suppose, but I’ll continue to put my trust in the soundness of an establishment with bouncer wearing a t-shirt that says “BOUNCER” because they got a properly identifying t-shirt and that’s enough credibility for me.

I don’t have any pictures from the bar, and I will leave it unnamed, because sometimes the whole “capturing people’s stories” can feel off and wrong, as if I’m a vampire sucking content out of people simply trying to live their lives who don’t deserve to have their moments of relaxation spun into a good yarn, at least not in the age of “everything can be immediately found online and blown out of proportion.”

I still have managed to do several short walks in Chicago when the weather breaks, including visiting the McDonald’s international HQ. The mother ship from which all forty-four thousand franchises have been launched, including the one I am writing this from.

That HQ McDonald’s is unique because it offers a limited array of menu items from across the world3, although I was more struck by how normal it was despite being constantly crowded with life-long McDonald’s corporate employees on their lunch breaks, or having work meetings. A vice-president of global franchise operations sitting eating a Big Mac next to a homeless guy nursing a coffee for five hours to stay out of the cold.

The inability to walk Chicago has been especially frustrating because I’ve been spending my free time reading the excellent book, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West by William Cronon, and I want to go see all the places mentioned, even if they’ve long ago been eroded by time. Such as the lumber yards of the 19th century (West of Halsted Street along the South Chicago River), Exchange Place, the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, and so much more.

The book’s thesis is Chicago made the Great West, and the Great West made Chicago, and untangling which wagged which is impossible because they needed each other. The other less explicit thesis is that Chicago made great things, and that happened because its leaders and citizens believed in making great things, like turning the dreary Chicago River, a slow-moving silty creek, into the best harbor on Lake Michigan, which even required changing the direction it flowed.

In that way, Chicago is the city that best illustrates America’s aggressive optimism, our fortunate geography, our excellence in engineering and finance, all which has resulted in us building the world’s largest economy, even if that means forever changing the landscape, eliminating the buffalo, denuding the surrounding forest of white pines, and turning the prairies into farms of imported invasive grains, and pastures of fenced-in cattle.

Chicago, as I wrote last week, is located on the knife’s edge of America’s two largest watershed drainage systems (Great Lakes, Mississippi River), with forests to the north for wood, and well-soiled land to the west and south for food, but unlocking that required massive engineering and investment, to construct what the author calls a second nature over the first.

Once Chicago created that second nature, building the canal across that knife’s edge (the Illinois and Michigan Canal), investing in a lumber industry in Wisconsin/Michigan, a grain and meat industry in Indiana/Iowa/Kansas, it became the beneficiary of all that was unlocked. A port town in the middle of the country where everything came together, unleashing a synergy that synergied like no synergy has ever synergied before.

I’ve visited the Chicago Board of Trade before, back when I was a banker and the pits were still mobs flashing their hands in obscure signals, and paper orders tossed into the center, so I don’t want to see it again, denuded of that, but the book makes a strong case the CBOT is the single most important actor in all of this.

A business boosters club turned financial powerhouse that unleashed another level of global growth that created the infrastructure and architecture of modern agriculture—futures contracts, commodity grades, crop insurance, which transformed not only the Midwest and Chicago, but all of the economy by turning crops into a global commodity4.

I was going to end this essay with a rant about how we in the U.S. don’t make things anymore, and how Chicago has lost its can-do optimism, starting with an anecdote from last Tuesday, when I jumped on the Red Line and found one car with a guy living in his own shit, sprawled out eating Chinese take out food, and the car smelled like it, and another with two guys openly smoking joints yelling about the Bears5.

That’s not fair to Chicago, because while it has its issues, it also still does make a lot of things, as any ride along the South Shore Line, or a walk through Calumet, Gary, or Hammond will show you6. As much as any place in the U.S.

Yet we as a nation stopped believing we could, and should, build great physical things, and once you stop believing, then that ability atrophies. Culture precedes institutions, that’s why England’s Industrial Revolution happened because they thought man could shape the world through reason and engineering. That is why Chicago changed the world, by reversing a river, building canals across watersheds, creating the financial architecture of modern agriculture.

But once financialization (the CBOT on steroids) trumped the physical—and managing global supply chains (with origins in other nations) trumped building them—then it didn’t matter if we made things as long as we could buy them. To extend the author’s thesis, once you move on from creating a second nature (infrastructure and all that follows) to a third nature (financial abstractions), which has fewer visible ties to first nature (the natural world around you) other than blips on a screen, then a lack of grounding shouldn’t be surprising. In that way Chicago can be partly blamed, since it created the monster that came back to eventually consume it.

Everyone I spent time with this week, including the homeless on the metro, is affected by a society that has moved on to third nature, and stopped investing in the immediate and local physical, social, and cultural infrastructure.

So I won’t blame Chicago for its current ills. It is still a great city, and arguably still America’s most American city because it is now dealing with very American problems.

It is why, when a foreigner in the future asks me where in the U.S. they should go to “understand America” I will tell them Chicago. Especially to a non dive bar dive bar on Karaoke night, when you see our optimism is still very much alive, just sometimes harder to see.

PS: I will finally be going to Duluth this weekend. I arrive on Friday (30th) and leave on Monday (2nd), so if you are in the area, please reach out to me. Unless the weather closes the airports. Again.

After that, and a few more American trips, I will be back to traveling the world, with a trip to Seoul, Okinawa, and Taiwan in March.

Until next week!

I’ve reached out to locals to get Scott and Judith more assistance, something they both want (“we could certainly use more help.”) and yet stubbornly refuse (”I am not letting anyone in my house!”). They are in that grey area of collapsing independence and withering resilience.

I’m always impressed with the extent of talent across the U.S., especially musical talent, and while I mostly find that uplifting, there is a sadness when you see a fifty-five-year-old office worker who could, with different luck, life choices, and breaks, be happily retired in the hills of LA after a thirty-year career that included two Platinum albums.

I rarely find these singers to be bitter—they’ve long ago accepted the arbitrariness of fame—and have found happiness in the weekly local Karaoke, a few gigs now and then, and family praise, but I wonder if I was in their shoes if I would show such restraint.

While listening to the various singers I kept thinking about my earlier post on Wittgenstein and God, where I write,

It is Wittgenstein’s last two lines that I’ve only really begun to understand, and appreciate, especially these last two months with the possibility of cancer, and mortality, hovering in the back of my mind,

I cannot bend the happenings of the world to my will: I am completely powerless.

I can only make myself independent of the world – and so in a certain sense master it – by renouncing any influence on happenings.

Almost everyone I intellectually respect, and admire, ends up with some version of this view—either via Eastern mysticism, stoicism, Catholicism, etc. They may not always pull it off, but they understand contentment in this life (and sometimes even fulfillment) requires a humility.

Maintaining that level of humility is never easy, but especially if you have an underappreciated talent. It is easy for me to say sure it is underappreciated by the marketplace but not by the community, and while it hasn’t come with monetary riches and global fame, it has come with the pride of an impressive night in a dive bar, or being admired by your friends, because I’ve managed to turn my hobbies into my career.

My early interest (math, physics, and history) were never adjudicated by the marketplace, like musical talent is, so I’ve never felt the disconnect between its accolades and my interests.

I’ve never been that drawn to the international menu, but if you are I highly recommend getting Gary He, McAtlas: A Global Guide to the Golden Arches. You can read my interview with him from a few months ago.

We’ve changed the world for better or worse, although in totality, despite the dramatic changes to nature, I side on the better, because humans will always human, and that means economic and technological progress, which means transforming nature for our benefit, although hopefully we have finally learned to be more nuanced in how we do that.

I chose the shit car because I didn’t want to get into an argument about Caleb’s lucky throw that probably would have ended in me getting shanked. And because I’m tired of my clothes smelling like weed.

I know it is just a single anecdote, but the situation on Chicago’s metro system is bad, and every time I’ve been on a metro or bus I’ve seen something similar.

It is worse than New York City because:

People just break rules willy-nilly, openly, and mockingly, with no consequences. On my train from the airport a guy got on, lit up a joint right behind me, smoking out all the abuelas who ran out at the next stop, handkerchiefs over their noses. Police at my stop told me they can’t/won’t do anything. Why give him a ticket when the judge will toss it out anyways?

Trains are less crowded, so a lot of homeless/vagrants, etc., have a whole car to themselves since few, especially women, want to get on alone with them. So you get lines with everyone in two cars, and the rest of the train effectively roving homeless shelters, each car housing maybe one or two people who are dealing with mental illness. They shouldn’t be free to roam the streets, and instead mandated to some form of treatment, including mental institutions, in-patient centers, and prison.

This last part could be an entire article, but suffice it to say that I don’t believe our policies in cities like Chicago are fair, either to the citizens who simply want a safe, clean metro system, or to those living on the streets themselves, who are not well served by being emancipated to wander the streets living in their own filth, doing drugs, and constantly tortured by their own internal demons.

The Chicago region quietly produces a lot of steel, about twenty percent of the nation’s, although it is about thirty-five percent less than it used to, but that isn’t Chicago’s fault because we as a country use a lot less steel than before, because we make a lot less stuff that needs steel. Much of that drop comes from offshoring, again not Chicago’s fault, but also because cars and appliances use less steel even when made here.

I spent a year in a Chicago suburb when I was 16 as an exchange student back in 1997, and I still can’t believe how lucky that placement was. It is truly the most American city one can experience. I have endless affection for the city, even for its windy and brutally cold weather. Thank you for another wonderful read.

"Chicago, as I wrote last week, is located on the knife’s edge of America’s two largest watershed drainage systems (Great Lakes, Mississippi River), with forests to the north for wood, and well-soiled land to the west and south for food, but unlocking that required massive engineering and investment, to construct what the author calls a second nature over the first."

A lot of that engineering and investment came from public sources. To give one example, the Mississippi is a lot more navigable and predictable than it was in a state of nature, thanks to the Army Corps Of Engineers.