Very low tech high tech travel

AI helped plan my upcoming walk, but that's about all it's good for

Next week I'm going to set off from Milan to try and walk the two hundred miles to Padua. This will be my tenth long-distance trek, which I written about before, and I prefer these move-every-day-with-everything-on-my-back trips, but organizing them is immensely frustrating.

Finding a viable route requires spending weeks scouring maps (Google, waymarkedtrails, Komoot, and other specialized sites) so that you don't end up on the side of a busy road playing a game of dodge the side-view mirror, or hacking through overgrown fields where there was once a trail. That means dropping pins in Google Street View to check if I really can walk along a road without constant fear of death, and then checking on available spots to stop each night, since I don't camp, having long ago lost whatever small romance I once found from sleeping on the ground without a shower.

You need to do this due diligence because while solitary paths through idyllic fields (like the cover photo) are what you want, hope for, and are usually claimed by trail guides, the reality is often more of the pictures below, which are neither enjoyable, interesting, nor safe.

Now I'm not aiming for walks entirely through fields, mountains, and small villages. If I wanted those, I could get them by taking up camping, or hiking well-established routes like the Camino de Santiago. Instead, I'm intentionally walking through heavily urbanized regions, like the Rhine and Rhone valleys, because I travel to learn about cultures, and that means being where the people have long been, and still are, which in Europe almost always means along river valleys1.

So I want and expect a certain amount of suburban sprawl, of intersecting tangles of roadways, of ugly boxy industrial warehouses, and even smoke-belching factories, because that, not pristine fields of rapeseed, is more the DNA of our modern industrialized world. Including in presumable quaint Japan, as I’ve found out in my three long walks there.

Seeing the unseemly connective tissue between the quaint instagramable downtowns is part of why I do these walks, because they are more the reality for most residents, and they are essential. Skipping past them in a train you miss the full picture of what it takes to keep our modern world up and running, and you can lull yourself into the fantasy that we’ve moved beyond the gritty past.

The left photo (from Fukuoka) is more the reality, the right more the anachronism, and so I expect and hope for a few miles each day of concrete and sulfur, and my choice of walking in Northern Italy, or the Po River basin, the most industrialized part of the country, was deliberate. Italy is the sixth largest manufacturing nation in the world, and that's as much of its identity as monumental buildings from eight centuries before.

So I knew I wanted to do a walk out of Milan towards Padua, but finding an exact route was harder than in Germany or France, because while the Po River was the basis of the region, it never had the commercial or navigable heft of the Rhône or Rhine, so it doesn't have the accompanying density around it.

After working through maps, discarding one route after another, I eventually landed on a rough schedule that I thought worked. Then I realized I was trying to solve a classic constrained optimization problem, but one with too much data for me to do alone, and that's precisely what AI is supposed to be best at, so on a whim I opened up Claude and typed,

"Can you come up with a walking path from Central Milan to central Padua, using trails, and low-density roads, going through cities where possible for a night's sleep and targeting no less than eight miles per day, and no more than seventeen?"

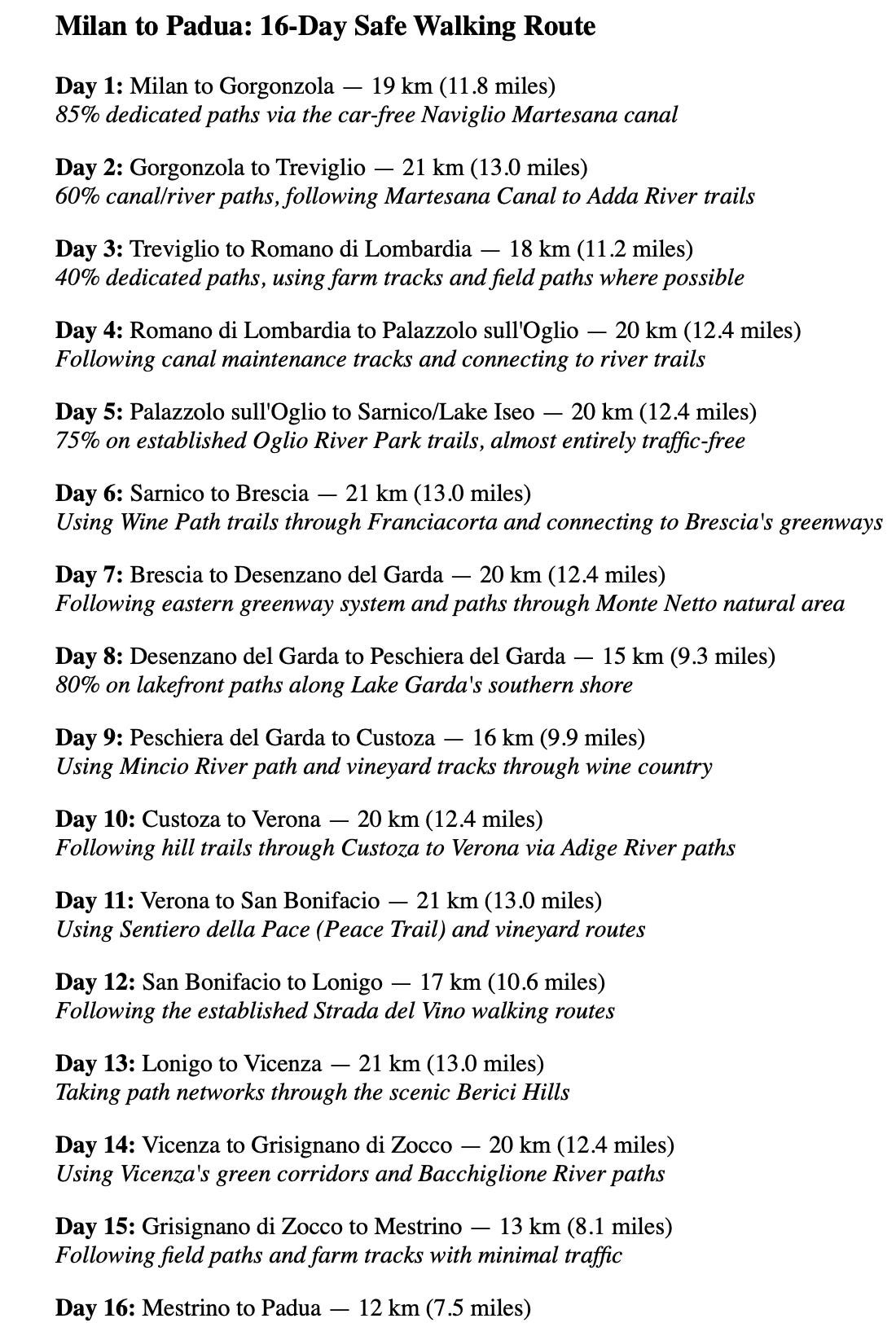

Its little engine whirred for a bit, pulling in all those webpages I looked at, some I've never heard of but wish I had, and spat out the following:

I was stunned because this is close to the exact path I'd eventually figured out, but after about a month of fiddling around.

Excited, I tried it on a few more parts of Europe I'd long wanted to walk but hadn't found an obvious approach, such as from Augsburg to Frankfurt, and within seconds, it came up with what seemed like a doable itinerary.

Except when checking some of the distances, they were wrong. Not by a small amount, but by orders of magnitude. Such as claiming one leg was four miles when it was forty-five. Over the next few days of testing AI more and more, excited that I'd found a tool that would open up all sorts of great walks for me, I saw how bipolar it is.

While it has a remarkable ability to sort through gobs of data, creating paths that I never found after days of searching maps. Then it goes and does the most idiotic things, like getting basic distances wrong.

This upcoming walk will serve as a test of AI. I hope it works, because I've long dreamed of walking from Liverpool to Brindisi, following the Roman and medieval trade routes. I would like to think the only thing stopping me is the planning. Ha!

While AI might end up being helpful for long walks, that's about all I see using it for, because one of the underlying philosophies of my travel (and life) is that fulfillment and enjoyment don't come by trying to optimize everything. Rather, the opposite. The best travel is when you go in with only a broad sense of what you want to do, and without detailed lists.

That includes this walk. So far I've only booked rooms for the first four nights, because I want the freedom to change things up, which I expect to do. I prefer the ability to shift, sometimes on a dime, towards what interests me. What that will be I've got no idea, but hopefully something I'm not expecting, and that's the point.

I've done little research or planning beyond my usual interest in the history of a region, and then booking rooms. I've no idea where I will be eating, or what I'll be doing each night. I'm not going into this trip with a list of must-see sites, or must-visit restaurants, or even must-stay-in towns.

I thought of this while reading the most recent piece by Lisa Abend, a wonderful writer, who takes a decidedly anti-tech approach to traveling. The concept behind her The Unplugged Traveler newsletter is to go into to a city blind, which currently means without using the internet.

The result is a style and philosophy that often overlaps with how I approach trips, although I would never ditch my phone, because it, among many other things, is my hiking map.

This passage particularly resonated with me:

"about how, in our food-obsessed age, the possibility of a bad or even so-so meal has come to seem like an unacceptable risk, and so we arm ourselves with lists and recommendations and annotated maps pulled from all corners of the internet as a talisman against a 'wasted' meal."

This fear of 'wasting' a meal, or an entire trip, ironically leads people to create exactly what they're trying to avoid, not literally wasted experiences, but stressful, anxious, and ultimately unfulfilling vacations, where you run around trying to maximize so much, you miss the part where you stop, relax, take stuff in, and live.

While I do use my phone and internet a lot when traveling, I rarely use it to choose where to eat, and once I'm in a restaurant, I put my phone down until my meal is over, because I do like to watch what's going on around me, and hopefully talk to people.

That tactic, of going into places with no expectations has worked for me. It’s how I found my favorite Izakaya in Japan, and it comes with these long distance walks, where I eat based on what ends up being around me.

That’s how I had one of the best meals I’ve eaten over the last four years, which was in France, when I found myself in a small town without any other options at the end of a long walk.

That enforced randomness is one of the single biggest reasons I prefer these long walks, which force you to use every stratum of a region, all of the connective tissue, not only the well documented and highly curated. Sometimes that ends up meaning having a disappointing meal, at least if your only measure is quality of the food.

When I see episodes of Bizarre Foods or Anthony Bourdain, while I appreciate what they’re doing, I tense up knowing how much preparation, how much research by an advanced team, goes into them. It might look fun, but actually recreating what they do isn't something I would suggest trying, even if it means going to the places they list, because those venues are now living off of the fumes of their brief fame.

The moments in those shows that work the best, especially on Bourdain's, have a lingering spontaneity to them, which decrease as the show matures into a paint-by-number franchise. Those moments are social, about the people met, with the food (or drink) secondary, and that's what I aim for.

So I'm not exaggerating when I say I go to restaurants entirely for the ambiance.

That's also why when I've been asked for the location of my favorite Izakaya in Tokyo, I've declined, not out of any hoarding, or selfishness, but because I can't recommend the food to anyone. It's OK, as far as that goes, but you can get far better food all over Tokyo, and that's what almost everyone wants when they go out to eat. I get it.

Yet I go there because it's now my regular, with people I know, who know me, but with so-so food, and that's not a transferable experience. You have to create your own, and I can't give you a detailed map on how to do that, nobody can, and that's the point.

So this upcoming two-hundred-mile walk will be a success, not based on whether I make it all the way to Padua, or what amount of great restaurants I eat at, but on how many of those non-transferable unique experiences I have, because it really is about the journey, not the destination.

Wait. That’s ending on a cliche, and I’m supposed to be deeper than that. Let me see if I can get AI to fix that.

Me: Can you find four less cliched ways to say "It's not about the destination, it's about the journey."

AI: Here are four less cliché alternatives to express that idea:

"The path shapes us more than where it leads."

"What unfolds between departing and arriving defines us."

"The stories collected en route outvalue the final chapter."

"The richness is in the pursuit, not the prize."

Each of these expressions maintains the spirit of valuing process over outcome, but with fresher language that avoids the overused journey/destination dichotomy.

I think I’ll stick to using AI only for helping me find my walking route, and anyways, cliches are usually popular for a reason.

PS: Readers would be right to push back that both Lisa and I travel for a living. In my case I do it almost all the time, so it's easy for me not to worry about wasting a trip since I have so many. If you get only two trips a year, and only get to go to Italy once in your life, it makes sense to take it more seriously than I do.

So, I wouldn't necessarily advocate for going in as freestyle as I do, but I would suggest you don't have to do as much as you think you do. At a minimum, leave yourself a few unstructured days to simply wander around, and allow yourself a few meals in places you choose somewhat randomly, or only by the feel of the place. Put down the phone for at least one day.

(If you find yourself along this route, please reach out to me. I leave Milan for Gorgonzola on Monday the 21st)

Forgot where I read it, but someone pointed out all of Europe is defined by all of it being within three days of the ocean. Either by horse, or by a barge on a river.

The joys of randomness in travel, the moments of genuine connections with people and cultures, are so much more rewarding than ticking off sites to see. But I think this is a lot easier to do when traveling solo. When I travel with others, I feel obligated to give them the experience they feel they need to have to justify the time and expense.

For instance, when I took my friends to Ireland in 2022 (I had been three times, they had never really been outside the States), we majored on visiting the big sites: Book of Kells in Dublin, Glendalough, Rock of Cashel, Cliffs of Moher, etc. All of these places are worth visiting (well, maybe give the Cliffs a pass at this point), but we all felt like we had been at "Ireland Epcot" for ten days. The only Irish folks with whom we interacted were in the service industry and had no real interest in speaking to American tourists. It all felt a bit packaged and sterile, and I think we all felt it would have been nicer to spend a few days in a smaller Irish town just living -- visiting the pubs, the markets, the churches, and wandering wherever whim took us.

I contrast this with my solo trip to England that same summer. I intentionally chose to base myself in Shropshire for three weeks, since it's a very rural and sparsely populated county. While I did sight-see, I spent most of time just wandering the countryside, hill-walking, and exploring villages. I never planned out a meal, instead just picking a pub wherever I happened to be. (I needed a car for this trip.) I encountered so many lovely English people while walking, dining in pubs, attending church services, etc. This was far and away a more memorable and rewarding travel experience and has set the tone for what I expect out of a trip going forward: go for at least three weeks, spend your time in one place, and don't plan things out with too much detail.

Great rec on Unplugged Traveler. I've used Lisa's approach to inform periodic walks I take in random neighborhoods near where I live. I don't get to do this nearly as often as I'd like - having two very small children will do that - but it's a good way to approach travel and exploration, and can be modified to fit one's comfort level.

Regarding trip planning, for people (like me) who cannot travel all the time, I've found a "one Big Thing per day, no more" rule works pretty well. This rule isn't absolute - typically I'll work in some days with zero Big Things and once in awhile a day with two. And some of these activities or sites are more time-consuming than others. But generally the idea is, you do the Thing (whatever it is) and leave the rest of the time mostly unstructured (sometimes with a vague plan in mind, but not always and the plan is easily changeable).

A good approach also is walk to and/or from the Thing, even if it seems kind of inconvenient. Like, some years ago I was in Rome and I would frequently walk in at least one direction to get to and/or from whatever Big Thing I wanted to see, even if there were other transportation options available.

Finally, returning to the same destination does relieve some of this pressure. I live in the Northeastern US and we have started taking annual trip to Montreal with the kids. It's an easy drive, my wife and I have both been there a bunch of times and we know we'll go again so we feel zero pressure to Do All The Things. We may or may not do some Things, but mostly we just wander around town, eat delicious food, have picnics, and let the kids run around at one of the many playgrounds. It's delightful.