As explained in part one, these are short write ups from my twelve years driving, walking, and bussing, around the US, that for various reasons haven’t been published before, either in my book, or articles from that period, due to sensitivity issues that have passed with time, or because the scenes don’t fit into a tidy box, beyond highlighting how central McDonald’s is for a lot of communities.

I’ve written many times about the importance of McDonald’s, as a community center, both in articles and in Dignity, and that hasn’t changed. I wrote this piece in my local upstate NY McDonald’s where two weeks ago an elderly woman showed up, who was living in her car in the parking lot.

She, like a lot of people between homes, used the McDonald’s bathroom to wash up each morning, and then spent the remainder of the day at a corner table about ten yards from me, bags of her stuff next to her, electronics of various sorts surrounding her, with a heap of cords snaking from every direction to an extended power strip at her feet.

She was a mess, smelling of waste, hair matted and knotted, legs covered in bruises, as was her car, which was about as full of garbage as a car can be, with all it’s windows blocked by discarded paper plates, cans, Styrofoam egg containers, tissues, books, and clothes.

She was quiet though, and I left her alone since it was clear she wanted to be left alone, sipping a coffee while writing loopy sentences in a child’s notebook, or else re-arranging the junk in the bags next to her or in the car.

A few days ago, she was gone. I asked the morning-shift floor manager, Noelle, what had happened to her. Noelle said, each night the woman would charge her car with a small generator she kept under her corner table, but someone had stolen it from the lot a few nights before. Noelle’s husband, a mechanic, heard about this and towed her car to his shop, where he changed the battery, then fixed a whole rash of other problems (belts, tires, wipers, fluids), all for free.

Noelle wasn’t bragging about this or looking for my praise, rather she understood that this is what a good Christian did. I knew she saw herself as this, given the bumper sticker on her car; I’d taken a picture of it six months earlier because I got a good laugh out of it.

They also raised a bit of cash to help her out, presuming she would use it to get where she claimed she wanted to go, which I posted about on social media the next day.

It was a feel-good story that with time became more complicated, and a reminder that helping others, especially those towards the very bottom of society, comes with a lot of nuance and pitfalls, even if it’s the right thing to do.

Two days later, after the repairs and the cash gift, the car reappeared, and she was once again in the McDonald’s at her table. Noelle asked her what was up, and she made some confused excuse, and then Noelle offered more help, telling her she should come over to her home after work where her husband could could help with the trash in her car.

She did come, after they had gone to sleep, and emptied half of the car’s trash across their front yard, before returning to the McDonald’s. Noelle told her the next day she can’t do that, and tried to see if there was someone in her life who she could contact, but she said there was nobody (other than a no-good sister a few towns over, who when called, never answered), and so Noelle eventually contacted the police, not to arrest her, but so they could get her help, for her own safety. As she said, “I can’t understand why there is nobody for her, why she is allowed to live and drive around in a car you can’t see out of. She needs help. Where is her family, where are her friends, where is anyone? She’s not safe living like that.”

In my brief dealings with her, it’s clear she’s mentally ill, and while she needs a home first, which given the New York system, is available (despite the bureaucracy, the homeless do have options in NY), she also probably needs to be in an institution, at least for enough time to be evaluated and if necessary, medicated, which I’m told she doesn’t believe she needs.

We don’t do that though these days, because involuntary treatment is seen as a human rights violation, even if the person is a clear threat to themselves (as she is) or others (I doubt she currently is, other than by causing a car accident).

I’ve not written about this issue before because my primary focus has been on the lack of organic support (family, community) in the US that most other countries have, and because it’s an ethical and political minefield, but at this point, after all I’ve seen1, and I’ve seen far far worse than this woman, I agree with Freddie deBoer that in the US we need to return to involuntary treatment, and even mandated institutionalization, for a segment of the homeless, both for humanitarian reasons, and for the health of broader society.

Or to put it in my framework, with the breakdown of the family- and community-based support systems, we’ve handed off responsibility for those with the least to the government, who in the case of the most destitute (mentally ill, homeless) have said, “It’s best we don’t get THAT involved, for blah blah blah reasons,” which has left a lot of people with no support, recourse, or consequences, beyond periodic imprisonment. No matter how some might try to spin the idea everyone, regardless of their mental condition, should be free to “choose a life of squalor, mental anguish, and even aggressive behavior on the streets” over mandated treatments, because of liberation or emancipation, it is not the moral, humanitarian, or just thing to do2. It’s well intention-ed cruelty.

As to the sensitivity issues, I left out a lot of content from Dignity, usually stories of criminal behavior, even though I had the individuals’ approvals to publish them. After the book came out5, I went back to try and give copies of the book to people who I’d met, and I did find a handful of them, and those I’d left out were disappointed, and those I included, but without pictures, were equally disappointed not to see their portrait in the book, despite being a photo of them shooting up, or living in squalor3.

That fits with one of the first lessons I’ve learned from what I do, which many young journalists find surprising, which is that meeting strangers is pretty easy and most people want to talk and share their thoughts, and the problem isn’t getting them to open up, but more often getting them to shut up, as long as you approach them with an open mind and treat them, regardless of their situation, as simply another person. Not as a victim, not as dangerous scoundrel, not as a story to “get,” but as someone you are genuinely interested in spending time with, which if you’re not, then you shouldn’t be interviewing people.

I’m leaving today for Reno and I’d thought of weaving the first story into my subsequent piece, but the McDonald’s where it takes place is now closed, which doesn’t surprise me, since it was the most chaotic franchise I’ve been in, and I’ve been in at least five hundred McDonald’s.

Misty and Scott (Reno, Nevada)

At six in the morning the McDonald’s across from the casinos is busy, but nobody inside would call themself a winner. Nobody would call themself a loser either, not at least at that moment, because nobody here had just blown a bundle on craps or poker or slots or the roulette wheel, since nobody in here had a bundle to blow. Maybe they would when their disability checks clear, but that wasn’t today. It was just a normal summer Wednesday.

The McDonald’s, like the pawnshop and liquor store on either side of it, is open twenty-four hours, providing those working in, playing in, or ejected from, the casinos on the other side everything they might need no matter the hour. It is drab, rudimentary, and filthy, with garbage-covered booths on either side of an aisle leading straight to a long bland counter at the back.

Only one register is open, staffed by an older black woman in absolutely no hurry, and the dozen or so people waiting, in a rigidly elementary-school-like straight single line, is a taxonomy of America’s dysfunctional, with the abandoned elderly, the crippled, the obese, the addicted, the distraught, the obese addict, the abandoned elderly cripple, and every other possible combination of each.

The only other visible staff is a Hispanic woman helping bag orders, who while united with her boss in a methodical insouciance, is her physical opposite — teen versus retiree, short versus tall, round versus lanky.

She is slowed down by ancillary requests yelled at her by customers in the booths, “Hey, honey. You got any Sweet ‘n Low, cause I can’t take Splenda on account of it bloats my feet?” sends her searching for a few minutes in boxes on various shelves, which she doesn’t find. “You got that spicy hot sauce for nuggets? “I put it in my coffee, I know, it is weird, but I like the bite it gives the coffee. Makes it taste expensive. It infuses it with a little class,” sends her crouching to look through another set of boxes on another set of shelves for another few minutes.

A man two back from the counter, sitting in a wheelchair festooned with tiny American flags duct taped to every available spot, holds tight to a dirty cup filled with change. When he turns to see who is yelling behind him, the coins spill out, rolling to almost every part of the floor. Unable to reach down he jabs at the coins with a cane. Nobody in line notices or helps him, busy yelling into their bluetooths or in their own thoughts. Eventually an old woman, worn in that way only a life on the streets wears one, collects the change for him, which he acknowledges by telling her God is great, something from her tattoos of Jesus she seems to already agree with.

When he gets to the front the cashier finally perks up, bounces a little, and leans over the counter to kiss him on the cheek, but he’s too low and too far away, and she knocks over a tray of straws, which spill to the floor with a loud bang, bringing a smile from him, and a “I haven’t seen you in a long time” from her, and then they talk about life’s complications as he tries to collect the scattered straws with his cane, which causes the coin cup to capsize again, which brings the cashier out from behind the counter to help collect the coins, and straws, and they keep this up for at least five minutes with no sense or concern about the fifteen or so other people waiting, which is seemingly fine to everybody but me, since nobody shows any frustration, or care, lost in their six a.m. thoughts.

A loud group comes in and collapses into a corner table. Six men, with tattoos and baseball caps with straight flipped bills, and one younger woman. She has bright red hair, tiny shorts, and knee-high stripper boots. They are all happy, laughing and joking, breaking into pretend fights. Their energy takes over the room, but nobody pays them much attention.

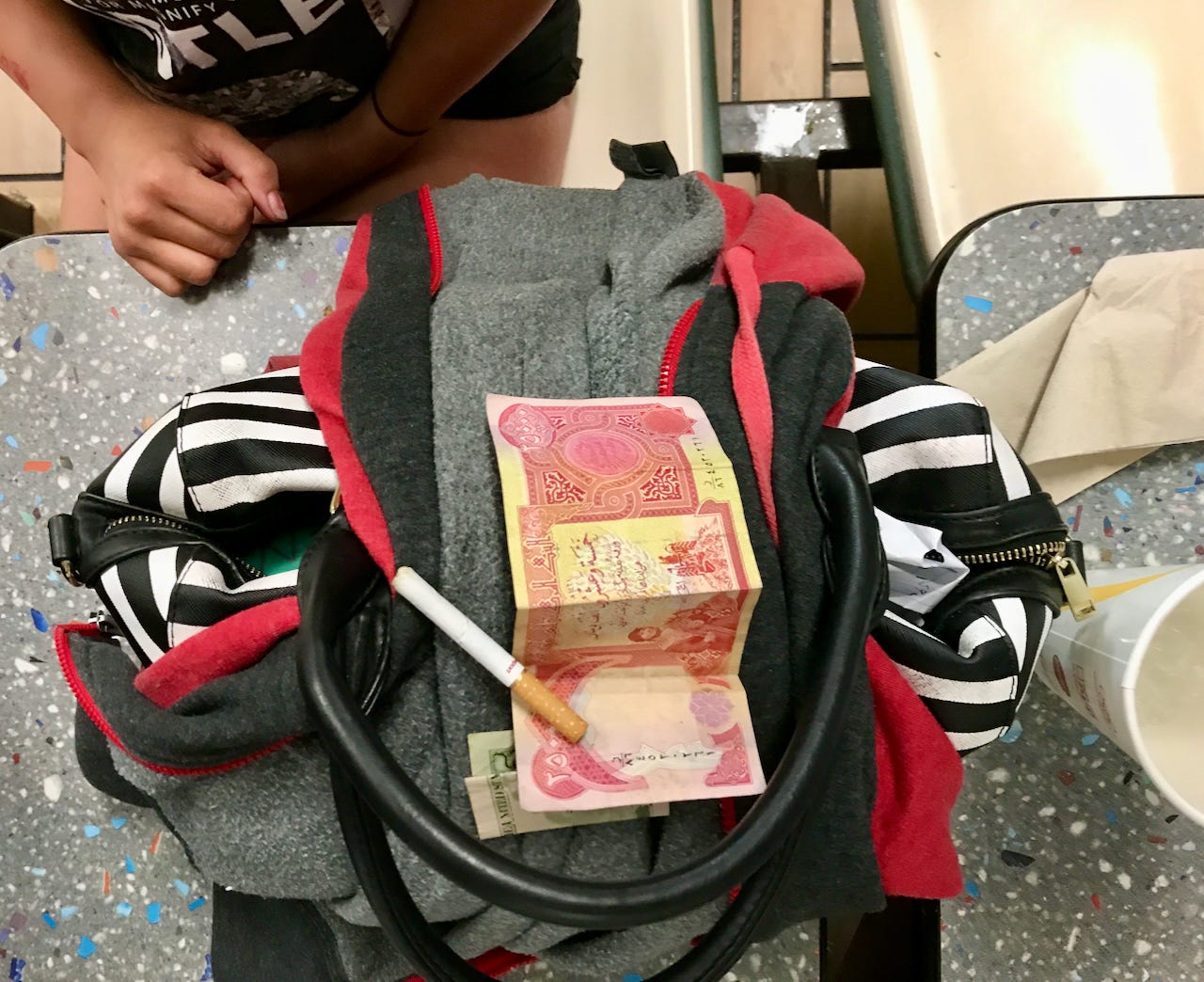

In the center of the table the young woman places a foreign bill worth 25,000, in whatever currency it is. She says she just found it on the sidewalk. They are abuzz over the bill, trying to figure out the value, “Google that shit. We probably millionaires.” They argue back and forth, each new bit of information from someone’s phone swinging their fortunes. Eventually they decide it is worth twenty dollars and they shift to figuring out how to sell it, or exchange it.

They spot me, the only person in the McDonald’s who they don’t know, and who looks like I might have some money.

It is an Iraqi Dinar note, that I explain is probably worth about six dollars, assuming someone will take it, but I will give them a ten for it. The woman, Misty comes over and sits with me, and pockets the ten dollars. Her boyfriend Scott follows, and then a young black man follows, who they ignore before he leaves. They explain they just met him a few minutes ago, “we partied together for a minute, but we don’t know him otherwise.” He eventually comes and asks me for money (I hand him a few bucks) and then leaves for good. The rest of the group, still pumped up, disbands, some going to stand in line, some to smoke outside, some to talk to regulars sitting at adjacent tables.