My first piece on Mongolia: Walking Ulaanbaatar

My second piece on walking Mongolia: Walking Darkhan

On my last day in Mongolia I was interviewed by Suren Ganbaatar, a twenty-seven year-old journalist. As I was walking across Japan I kept thinking about the limitations of being a traveler, and no matter how much you try to understand a place, there will always be things you miss, and things much better told by those who grew up there.

So when I got back to the US I reached out to Suren, and asked if I could interview her, via email.

Below is a lightly edited version of our exchange. I hope to do this more often, in other countries I visit. To broaden the perspective of this newsletter beyond just me.

I hope you find it as interesting as I did!

Hi Suren. So let’s starts this dialogue off with a quick first question, to set the stage. Tell me a little about yourself, however you want, with basic information, who you are, what you do, where you were born, parents, etc.

When Mongolians meet a person, they ask their name and then always say "which province are you from?" It is customary to ask. But I tell them "No province" because I was born and raised in Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia. My name is Suren. Would you believe that I was born at home? I was born in the hands of my grandfather in a one-story mud house located in the Bayankhoshuu ger neighborhood on the western outskirts of Ulaanbaatar. My grandfather is not a doctor or a midwife at all, but as an elderly Mongolian man who knows science of medicine and his traditional heritage well, he had the wisdom to deliver his daughter’s fourth child safely. In 2002, the year I started first year of elementary school, my family moved from a one-floor mud house in the ger district to the 7th floor of a blue 12-story apartment building in the 4th districts, which was known as the city center at that time. It is said that during the Socialist era, the apartments in the 3rd and 4th districts, known as the "Gift Building," were built as a gift to Mongolians by the leader of the Soviet Union, Leonid Brezhnev. The Soviets built many large neighborhoods, factories, schools, and kindergartens in Ulaanbaatar. And so my elementary school life was spent in a comfortable apartment in the city.

Around the same time as my childhood, in the 1990s, the democratic revolution took place in Mongolia, and with the start of privatization, many people began to live by trading abroad. My father and mother, who worked in the government service, lived for a while trading between Russia and China. At the moment, my father realized that working internationally was necessary for a family of four, so he started working around the world, including South Korea, Japan, England, and Ireland.

After graduating from high school, my parents were chosen by their peers to study as engineers and economists in the Soviet Union, so they spoke Russian well. On the contrary, I graduated from a private high school with a special Chinese language program and obtained a bachelor’s degree in Journalism and English Language Translation at the National University of Mongolia.

Now, in her free time, my mother watches Russian TV channels at home, and I watch English or Chinese dramas to refresh my language. Many youth of my generation taught themselves English by watching the American series Friends. I watched it every time I had breakfast and watched all ten seasons five or six times.

The year I entered middle school, my father came back home and we sold our three-room apartment in the city center and bought a house with a grocery store along the road in the “Sharkhad” neighborhood on the eastern ger district edge of Ulaanbaatar.

It is very interesting working in a grocery store. People with different lives who live in the nearby streets, dealers in the nearby car market, and buyers who come to buy a car will be there every day. There were very few people who could buy a net full of food. Most household shoppers struggle to get enough food for the day. It is common to sell a loaf of bread in slices. Also, every day several people write in the "debt book" to get food. When my mother worked as a saleswoman, she continued to lend goods to people she knew, but two years later, our store suffered a loss of 5 million MNT. At that time, in 2008, one dollar was equal to 1,000 MNT, while in 2023, one dollar was equal to 3,442 MNT. And so it ended our grocery shopping “career.”

My father then decided to go to America to sort out his life, and the visa was successfully issued in the same year. For ten years, my father lived in the United States and his family lived far away in Mongolia. The difficult situation in the ger district, which had been unnoticed before, began to be felt after my father’s departure. I realized that for teenage girls, living in a ger district in the winter is not a very desirable dream.

The water well is nearby, but there are many difficulties, such as not being able to bathe whenever I want, waking up in the morning to find a 100-liter bottle of water frozen, heating the water on the stove after dinner to wash the dishes, and frequently going out to the toilet in the freezing cold. The coldest period of Mongolia’s winter occurs in January, when it reaches minus 30 degrees Celsius. In some parts of the country, it can even reach minus 40 degrees Celsius.

Imagine that my sister once warmed up the bed before going to sleep by ironing it because it was too cold. It seems funny. Children, dreams, and the future are always good things, so at that time we did not think of all this as suffering. But in the summer, it’s really nice to live in a ger district.

Currently 205,000 households in Ulaanbaatar are living in ger district, and 83 percent have already applied to the government for housing within the redevelopment of ger district.

Suren, this is so interesting, I have so many questions. Tell me a little about the grandfather who delivered you. Where was he born? Did you know him very well? If so, what was he like.

Now to your childhood in the Ger district. I don’t think many Americans have any idea what it’s like to live in Mongolia, much less the Ger district. So tell us a little more about daily life in the Ger district. What you ate. When you bathed. How you bathed. What you did at night for fun.

When we spoke in Ulaanbaatar, I mentioned how it was common to see children as young as six walking alone home. Did you do that? What was it like? Were you afraid?

People live very close together. In the Gers themselves, there seem to be no privacy? What is that like? It must have been odd for you to watch Friends, and see their nice apartment. Even though you were in an apartment at that time, I know the Soviet apartments and they also don’t have a lot of space or privacy.

My grandfather was born in 1930 in the family of herdsmen in Zavkhan Province, Mongolia. At the age of twenty, he moved to the city of Ulaanbaatar to work as a truck driver. The current city of Ulaanbaatar was founded in 1639 under the name Urguu, and since then it has changed its name four times. Since 1924, it has been named Ulaanbaatar. My grandfather was an uneducated truck driver, but he knew his heritage well, and he was a man of medical and various kind of knowledge. He had a strange kind of bald head, always wore a Mongolian traditional outfit named ‘deel,’ and smoked ash cigarettes often. I don't know much about my grandfather because he died when I was eight years old.

When Ulaanbaatar was called Urguu, it was the center of Mongolia's religion and government, and it was a city made up entirely of gers. Residential areas were built and industrialized in the early 20th century, and the current image of the city was formed in the 21st century. All the gers and houses in the city face south, forming a long row of gers because Buddhism, which is the main religion of the Mongolian nation, has a tradition that homes should face south.

The first European-style two-story building in Ulaanbaatar was built in 1863-1864 for the Russian Consul Minister. Since then, multi-storied buildings have been erected in Ulaanbaatar.

Now, parts of the ger district area are located on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar. Ger neighborhoods can be classified into one-story houses, gers, and two or more story houses. As for me, I lived in a two-story house. When we first moved in, water and heat problems were solved, the house had a bath and electric heat, which is considered the same as a private American house. However, since there is no integrated home heating network in Ulaanbaatars ger districts, after two years, it became very expensive to heat a large two-story house with electricity, so we had to burn coal and heat it with a stove. Also, since the ger district is not connected to the water network, water needs to be transported from a nearby well. The need to get 100 liters of water two days a week was difficult for our family without a private car in winter.

Most of the families in the Ger neighborhood go to the public bath located on the nearby street whenever they want to take a hot bath. The families in the Ger neighborhood are very close, so they know their neighbors well. The children of the family played together in the middle of the street, sometimes ate food together, and had a good “neighborly bond” where they helped each other, starting from asking for salt. But now, times have changed, neighborhood ties have become distant, and the families on the street no longer know each other I guess. Children from the neighborhood often go to nearby schools, so they know each other well and are often in the same class.

In Ulaanbaatar, children learn independence very early. Parents usually work at the same time and come home at 6:00 in the evening, while middle school children study in two shifts, in the morning and in the afternoon. Therefore, it is difficult for parents to send their children to school themselves. Children who live with their grandparents are taken to school by their grandparents, while other children have to go to school by themselves from the first grade. As for me, my brother was three grades above me, so he used to deliver me to school. (When I was in first grade, we lived in an apartment.)

I learned to go to school by myself in the third grade. The same is true for children living in the ger district. Children are independent from childhood, often walking to schools far away by themselves and even travel far away by bus. In Ulaanbaatar, child care services are expensive, so not every family can afford them.

Mongolian ger have different sizes, but they are arranged like one room. Therefore, members of multifamily households have very little personal space. Mongolians have long had a custom of building a separate house next to their home when their children reach adulthood.

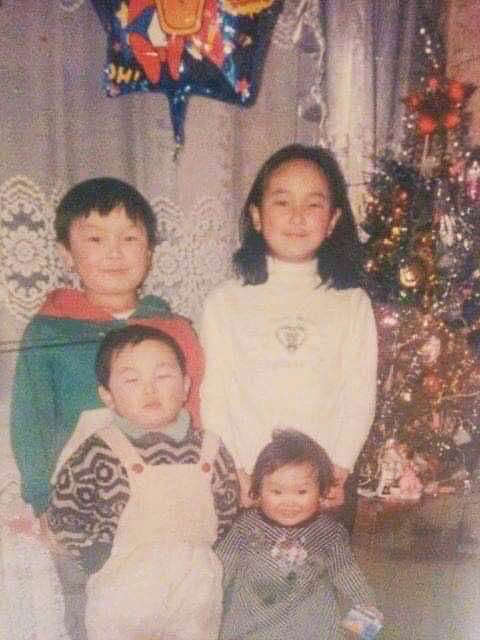

When I lived in a three-room apartment with my mother, father, two brothers and a sister, I always dreamed of having my own room. In Hollywood movies showing the lives of teenagers, teenagers decorate their rooms beautifully. Many years later, after my older sister and older brother got married, I was very happy to have my own room. But I have very close and warm memories of the time when we all slept together in the same room. Many rooms and walls seem to isolate us and make us colder as time goes by.

Europeans make their children sleep in different rooms from infancy, and they have their own rooms from a young age. For Mongolians, being together in one room has the disadvantage of not having personal space, but I think it has the advantage of creating a warm atmosphere to the family.

I’ve noticed how important family is to you, in your answers, but also from my time in Mongolia. You wrote about your father being abroad a lot, including in the US for ten years. What was that like, for both him and your family? What did he do, and where did he work. I’m sure you all missed him.

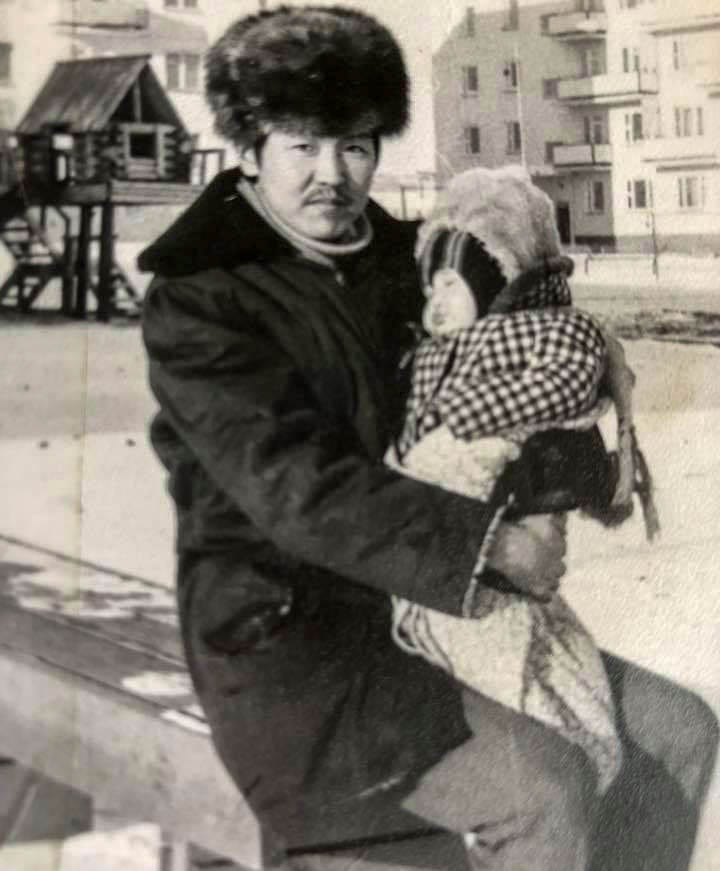

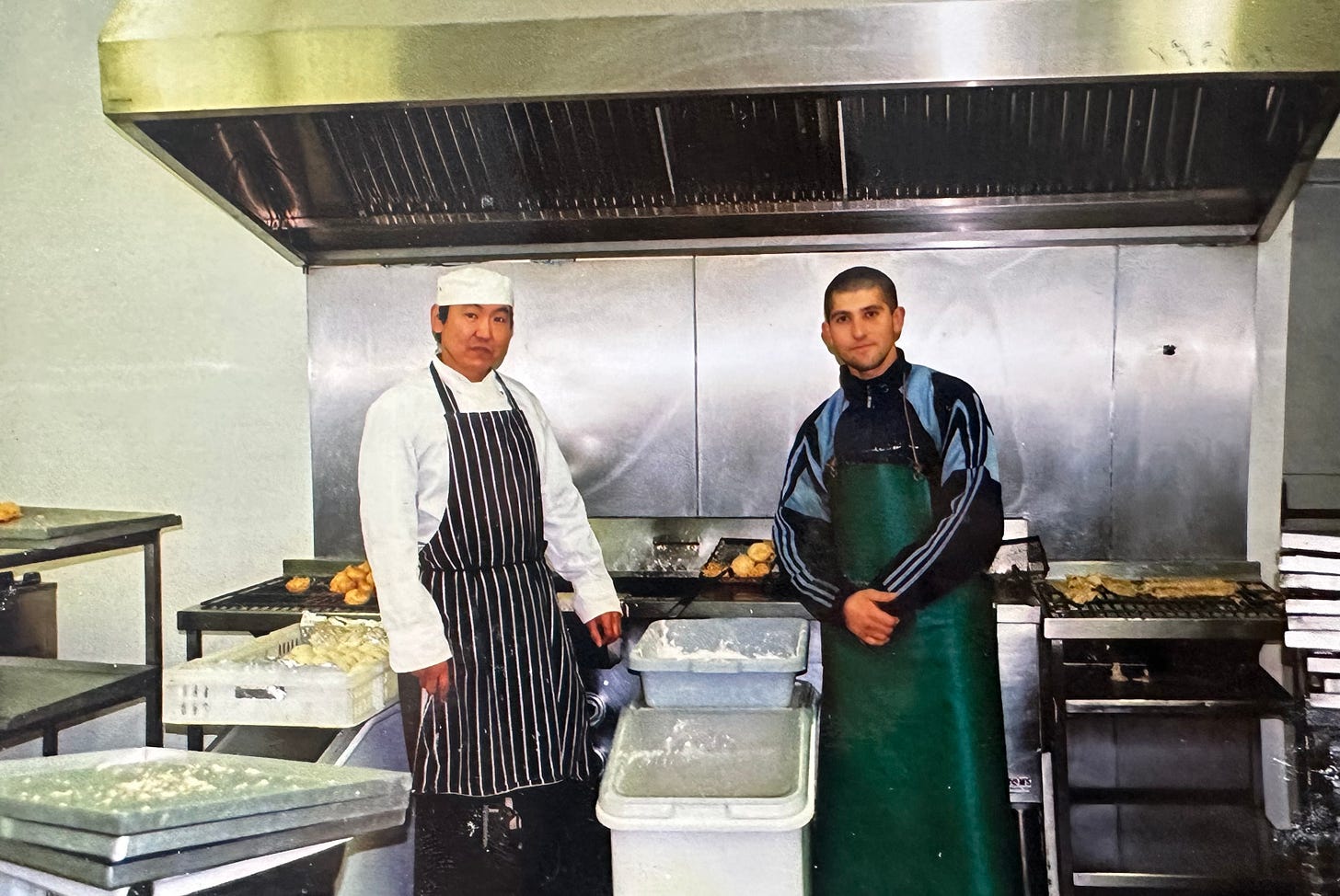

My father was born in Ulaanbaatar in 1961 and studied engineering in the Soviet Union in the mid-1980s. My parents met when they were students and got married. My father was an engineer at Mongolia’s leading timber industry during the Soviet era. In the mid-1990s, when Mongolia announced its democratic revolution, national factories were privatized, one of which was the factory where my father worked. So my parents bought goods from neighbors in the south and north and came to Mongolia to sell them. Subsequently, my father went to work in South Korea, Japan, England, Ireland, etc., and came home '“permanently” when I was in middle school. However, after two years of living in Mongolia, he went to the United States, and after I graduated from university and got a job, he came back to Mongolia, 10 years later. Dad lived first in Washington, then in Chicago.

At first, he worked as a part-time construction worker and soon became a chef at a sushi restaurant. When I was little, my father used to send us postcards every New Year with a picture of the city he visited. I didn’t understand this when I was young, but now that I think about it, I know very little about my father. My dad couldn’t be with us through our childhood, our graduation, my first date, and my first day at work. Instead, my father paid for our tuition, a laptop to write our graduation thesis on, and a dress for my first prom with his hardworking salary. Social instability and economic recession stole the time we spent with my father, but it didn't even remotely destroy our love for our father.

I’m also curious about how life is different for you and your brothers. Is it very different to be male vs female?

Mongolia has not fully achieved gender inequality, but it is trying to achieve it. As in most countries, women’s salaries are lower than men’s: The average salary of male employees in Mongolia is 2.1 million tugrik and the average salary of female employees is 1.7 million tugrik. Mongolians in rural areas prefer to send their female children to university if they have two children; there are more uneducated and unmarried men in rural areas. Local women come to Ulaanbaatar to study at the university, then settle in the city and have families. But the fact that the men stay in their communities has made single women rare in the countryside, and it has become a public concern. Sixty percent of university teachers and students are women. The school with the biggest difference is the Mongolian State University of Education, where the gender ratio is 82 percent female and 18 percent male.

In my family, everyone was lucky enough to go to university.

Another gender issue is that the life expectancy of men in Mongolia is 10 years earlier than that of women. Fifty-two percent of Mongolian men die before reaching the age of 60. The average life expectancy of Mongolian men is 66 years, and the average life expectancy of women is 75 years. Also, men commit suicide 5.2 times more often than women, which is the third highest rate in the world.

One more question. This is a more philosophical one. I hear in your writings something I noticed in Mongolia, and across the world, especially from people your age, both a love of where you come from, and what it means to be Mongolian, but also a desire to see the rest of the world, and maybe even leave it for good. Is this something you think about? The tension between the two desires, or is it something you don’t have, but maybe you see amongst your friends?

In my opinion, Mongolian youth of my generation can be divided into two groups. In the first part, young people who are tired of injustice, economic decline, corruption of politicians, and insufficient salary and income, want to run away from their home country and dream of going “anywhere” in order to earn enough salary.

The second group are dreamers who want to get a quality education in their desired profession abroad because they cannot get a quality education in Mongolia. It is because if you get an education abroad, you will be able to work with a higher salary and a better life when you return home. As for me, I want to get a master's degree in children’s book illustration, but Mongolia does not have a master’s program in this field. Also, the Mongolian children’s book market is very limited. I want to study because if I get my master's degree in this field internationally, it will open up many opportunities for me to work in the global market.

What about your mother?

My mother was born in 1961 in Khovsgol province, Mongolia’s most popular tourist area, and graduated in economics in the Soviet Union. She has worked in the public service for more than twenty years and is now retired.

Everyone who has heard your story about learning English from Friends thinks it’s great. Why Friends? If you have watched it 6 times, you must have some strong opinions about it. Who is your favorite character? Do you have any “Friends hot takes?”

When I was a student, I watched an episode of Friends on TV somehow and liked it very much. At that time, we didn’t have internet or computer at home, so after school, I sat in internet cafes and watched the TV series. Soon in my third year, I got my first laptop, but I had trouble finding the series on the internet. At that time, I hardly knew about Netflix or Spotify. But for the past few years, I’ve watched my favorite series on Netflix almost every day for breakfast and finished six times. I started watching it to improve my English, but I found it really funny and interesting, and the characters have become an important part of my life. I like Phoebe the most. It’s amazing to be curious, weird, funny, good-hearted, and believe in magic, even after a difficult life. I don’t know if she’s like me or if I just watched Friends and became like her (hehe)

What do you think is the thing most foreigners get wrong about Mongolia? The ones who visit, and then when you see Mongolia in movies, or read about it in books. As someone who has visited a lot of the world, I think it is a unique and special place. I’m sure if you grow up there you both see that, and then see another version of it. What would you want to change most about Mongolia?

I just want to change the political situation in Mongolia. Politicians are greedy for power, corruption is increasing, Mongolia is burdened with debt, and the economy is deteriorating, so young people dream of leaving the country. If the decision-makers in Mongolia were smarter, young people would be able to work in their country and live with their families. I also want to improve the quality of Mongolian education and provide equal access to quality education.

Last question. Do you spend much time in the countryside? Like during summers, or to visit relatives. If so, how is it different?

I like to go to the countryside during seasonal holidays or during the warm summer season. Since there are 21 provinces in Mongolia, I have only traveled to five of them, so I do not know Mongolia in its entirety. Mongolia is an interesting country with cold Antarctic climate, African desert, beautiful nature like Switzerland, mountainous area and low hills. Only my very distant relatives live in the country, so I don't know them very well, but when I travel with my mother, I visit them.

I want to thank Suren for this conversation, which, given our timezone differences, I hope we pulled off. I could ask her thousands more questions, but I thought I would leave it to you readers to ask any questions you want in the comments, and either Suren can answer directly, or I can forward the questions to her and post the answers myself (twelve hours later, given the time differences!)

Let me also know if you want more of this type of interview going forward.

Until next week. Have a great Thanksgiving!

Hi Chris, thank you for interviewed me. I really enjoyed our conversation ✨

Fascinating Chris,

Odd isn't it how as both the Soviets and the West encroach they both seem to accelerate the atomisation of the social bonds of traditional ways of life. It was ever thus I suppose. A great interview opening a window into a life it is hard to imagine.

Suren seems brave and inspiring. I wish her all the best.