Why walk? (Part two, How to Walk 12 miles a day, will focus on answering a lot of questions on logistics I have gotten.)

On my first day in Brooklyn (1993) I took the subway from Brooklyn Heights to its terminus at the tip of Coney Island, then walked the ten miles back.

I had never been in Brooklyn before and wanted to see what the town I was moving to was all about. While there was certainly tons of travel guides available, I figured the best way to understand it was to walk its length

It worked. In that first walk I learned Brooklyn was a loose confederation of very different working class neighborhoods, held together by subways and buses. Russians and Ukrainians dominated Brighton Beach, African Americans in East NY, Orthodox Jews Midwood, Caribbeans Flatbush, Mexican and Chinese Sunset Park, and even a small lingering Norwegian community in Bay Ridge.

I liked it so much that I kept up these long seemingly pointless walks through New York City, for my twenty years there. Walking from my apartment to JFK, or my apartment to Shea Stadium, or my terminus walks from the end of a subway line back to my apartment.

To be cliched, the beginning and ends of the walks didn’t really matter, but the fun is what and who I found in between. Things like pigeon keepers, bike clubs, cricket matches, guys scrappin cans, Thai wats, kids playing in hydrants, and so on and so on. People just living their lives, in very different ways from me.

Things I wrote about more extensively here and here.

I use this same approach when I am in any new city. On my first day I literally walk across the city, to the extent it can be done. I choose a route after spending a few hours on Google street view, then change it, often dramatically, along the way. I usually end in a bar, restaurant, church, or all of the above, before taking a bus back. The next day I do another cross town walk, but in a different direction, filling in the blanks from the prior day’s walk.

Then, over the next week(s), I walk between 10 to 20 miles per day, picking and choosing from what I have seen before, highlighting what I like, what I want to know more about, refining the path, till by the end of my trip, I have a daily route that is roughly the same.

While that is certainly not the most efficient way to see a city, it is the most pleasant, insightful, and human. I don’t think you can know a place unless you walk it, because it isn’t about distance, but about content.

Cars suck for that. They are a brutal way to get to know a place. A literal metal bubble that cuts you off, zooms your through, and then dumps you in another bubble of your choosing. A wall between you and the world.

Bikes are much better. They are more open, bring you closer, allow you to stop more, but they still cut you off from so much, mostly by bogging you down with gear.

But it is much more about the attitude both bring with them. Being rushed (by car, bus, metro, bike, or whatever) from one tourist destination (must see!) to another, gives a highly choreographed and narrow view of a city.

Every large global city has a few upscale neighborhoods that are effectively all the same. It is where the very rich have their apartments, the five and four star hotels are, the most famous museums, and a shopping district with the same stores you would find in Manhattan’s Upper East Side, or London’s Mayfair.

The only difference is the branding. So you get the Upper East Side with Turkish affectations, or a Peruvian themed Mayfair. The residents of these neighborhoods are also pretty comfortable in any global city. As long as it is the right neighborhood.

It is the rest of the city, which is the vast majority, that is interesting. Because it is truly Turkish, or Ukrainian, or Indonesian. Not American with different flags.

That is the part of the city you often miss by car or bike, and you see when walking.

Because walking forces you to see a city at its most granular. You can’t zoom past anything. You can’t fast forward to the “interesting parts.” It is being forced to watch the whole movie, and more often then not, realizing the best parts are largely unseen by tourists.

Walking also changes how the city sees you, and consequently, how you see the city. As a pedestrian you are fully immersed in what is around you, literally one of the crowd. It allows for an anonymity, that if used right, breaks down barriers and expectations. It forces you to deal with and interact with things and people as a resident does. You’re another person going about your day, rather than a tourist looking to buy or be sold whatever stuff and image a place wants to sell you.

By walking through a city, you meet the people who live there, and engage with them and their culture, on their terms in their environment. It allows you a small window into how they live. How they think about and experience the world. Consequently, it can change how you see the world.

When I was in Istanbul, everything and everyone told me to go to the Hagia Sophia. I did go, eventually, and it was beautiful, and you should see it, but it is a museum at this point. A very crowded one ringed by idling buses spewing fumes, tourists trying to do a quick walk through so they can check it off a list, and locals trying to sell you overpriced and silly stuff.

It raises a Ship of Theseus paradox style question. Does the Hagia Sophia, after so many changes, still have any of it’s aura remaining? Or is it now, after so many changes, so many tourists, a vessel devoid of anything but a place to be seen?

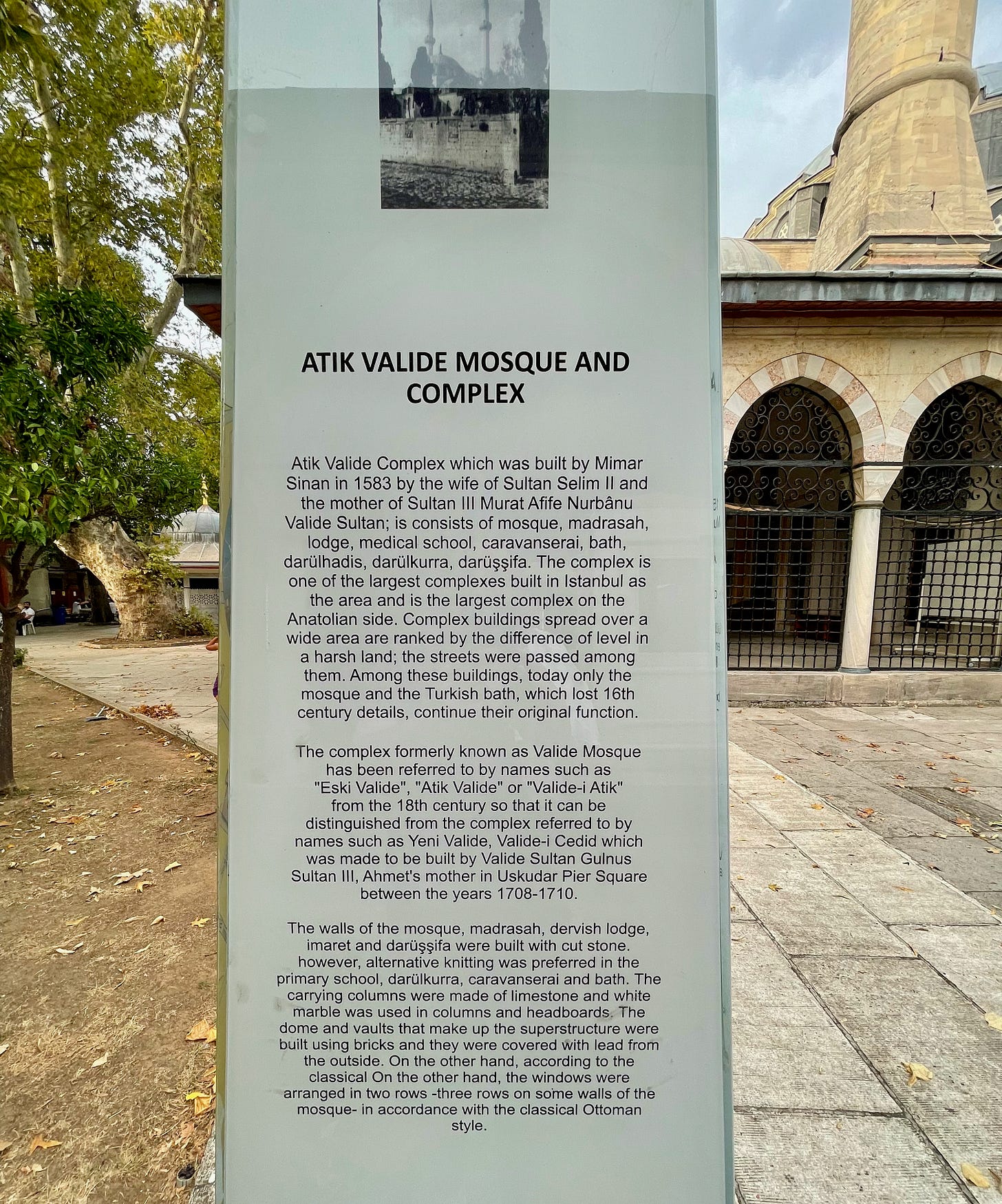

I only went once to the Hagia Sofia, and didn’t have much interest in going back. In contrast, I went almost daily to the Atik Valide Mosque in the Selmasiz neighborhood, which I had only found because during my first day’s walk across the Asian side, I was driven through it gates by fatigue, heat, and a desire for a little less noise.

That wasn’t entirely accidental. It was designed, and is still used, as protection against the heat, fatigue, and noise, among other things.

Like the Hagia Sofia, it has plenty of history (built in 1583), is beautiful, but unlike it, it is still a very active part of the surrounding community. Which is kinda the point of a house of worship.

Over the month I was in Istanbul it became a daily stopping point, and there was always something going on inside the walls, no matter what time of day. Either prayers in the mosque, or kids playing soccer in the courtyard between religious lessons, or families sitting on blankets having picnics, or the very elderly and the handicapped being provided for.

Almost every day someone gave me a glass of water, tea, and/or a snack. One particular hot day, while sitting in the courtyard catching my breath from the steep climb up to it, a group of women brought me plates and plates of food that only stopped when I pantomimed that I was about to explode.

Near the end of my stay, a barber across from the mosque, who I passed by daily and sometimes saw praying in Atik Valide, finally lured me inside to have my then very very long hair cut and my beard trimmed, at the strong urging of the same women in the courtyard who served me food. I believe they tried telling me I was both too scruffy looking, and the long hair didn’t work in the heat. But they didn’t speak English. Nobody in the neighborhood did.

Atik Valide wasn’t the only mosque I visited daily. There were three or four others that became part of my walks, and they all were similarly elemental to what a Turkish neighborhood is.

I’m not deluded enough to think that during that month I had become even a tiny part of this particular community. But it did give me enough of a sense of what went on, both in the mosque and the wider community, to gain huge respect for the Muslim faith. Especially how integral and integrated it is in working class communities, as well as how generous and supportive it is to the residents.

In Selamsız, Atik Valide provides people a place. A balance to the mundane. An aesthetic escape. They can walk through the mosque gates and become part of something beautiful. Both a physical community, and a higher purpose.

That lesson has been one of the biggest of my last three years. I eventually will write more about this (hopefully when I walk Amman Jordan), but it has fundamentally changed how I think about faith and its role in a society.

That is not something I would have learned from just taking a cab to the Hagia Sofia.

A beautiful meditation. Thanks for sharing. This is how I've tried to approach visits to big cities, and probably why I've been attracted to less glamorous, lesser-known places that others tend to dismiss (Paraguay, for example! You should go there; Zaragoza; the "Grand Canyon of Pennsylvania). Maybe because I'm from Baltimore, a classic second- (well, maybe third)-tier city that has a lot more going for it than meets the eye and headlines would suggest.

Thanks Chris, so enlightening, during lockdown with my daughter who is 50 years younger than me and was home from college I walked all the quarters of the West End and City of London. I have lived in London since 1975 but discovered so much more than ever before by being systematic and having the time to literally be drawn up blind alleys.

I am fairly new to your writings but enjoying them enormously.